Uropi: Une histoire d'aubergines - U storij ov balʒàne - Aubergine story

★ ★ ★

* Uropi Nove 59 * Uropi Nove 59 * Uropi Nove 59 *

★ ★ ★

★ ★ ★

U storij ov balʒàne

★ ★ ★

De Franci vord "aubergine" we, be pri viz, duf od soli polde, ov Provensu merkade id ov campihostias (auberge in Franci = hostia), odvèn in fakt od u seni Persi vord bādemjān, we som ven od Sanskriti vatin-ganah. Bādemjān davì al bādinjān in Arabi, in wen al se de artikel, ba we vidì inlesten wim u talad in Katalàni: albergínia, we davì de Franci vord aubergine. Espàne id Portugane sì semim bunes analiste - unvos se ne siudad - apcizan de Arabi artikel od de nom, wa davì berenjena id berinjela. De majsan tem, de Arabi artikel vid kleven a de Espàni nom wim in alcalde (major) < al qâdī, alcoba (alkova) < al qúbba, algarabía (garabij) < al arabîya (Arabi linga)… De Franci vord avì u gren ustèl ki Germàni polke we konì ne di soli vegùm, id inlestì de vord wim sul in Doski, Nizilandi, Swedi, Dani, Norveji: aubergine, id oʒe in Engli wo je vid korenen pa u lokal prodùt: eggplant, "oviplànt", andubim par da vegùm se valgim oviformi.

In Itali un moz bespeko un interesan fenomen wen un find os in Uropi: krosen rode o micen vorde: de vord melanzana ven od de krosad intra de Arabi vord bādinjān id de Itali vord mela, apel. In da veti teme, un siudì nomo "apel" eni novi frut o vegùm, wim dik no pomodoro = tomàt (= gori apel o priʒe gori frut), de Franci o Nizilandi pomme de terre o aardappel = "teri apel", po nomo wa sì po Arawake batata, id pos po Espàne patata. De Greci vord vidì versemim inlesten od Itali, par u krosad ki de vord apel: μήλο"mîlo" avev priʒe daven "mîlitzana".

Ba de storij balʒàni fend ne zi. Ka usvenì in Balkàne, valden davos, nerim intalim, pa de Osmani imperia ? Turke os inlestì de Arabi vord bādinjān disforman ja in li siavi mod: patlıcan (c vid usvoken [dʒ] in Turki). Je se interesan bemarko in pasan te Azeri, we se os un Altaji linga mol neri a Turki, inlestì de vord direktim od Persi: badımcan. De Turki vord disspanì su tal de Osmani teritoria id oʒe uve: Bulgàri patladjan, Albàni patëllxhan, Serbi id Kroati patlidžan, Hungàri padlizsán…

Maj dal do nord sì distensan de imperia tsaris: za os de Rusi vord баклажан "baklaʒan" sem mo un inlèst od Turki; un find ja os in Bielorusi id Ukraini, id os in Polski: bakłażan, Tceki id Slovaki: baklažan, in Latvi: baklažāns, Lituvi: baklažanas, Esti baklažaan id Uzbeki baqlajon*.

De Persi vord som bādemjān usvolpì inia Iràn id alten Persivoki teritorias, vidan bānjān we sin obe tomàt bānjān e rumi (balʒàn od Roma), bānjān e sorkh (roj balʒàn), id balʒàn: bānjān e siāh, bānjān e sosani.

Du vorde staj misteric: Romani brinʒal id Malti brinġiel. De somivad ki bādemjān id ji posgene sem sat klar, ba od kele lingas vidì lu inlesten ?

★ ★ ★

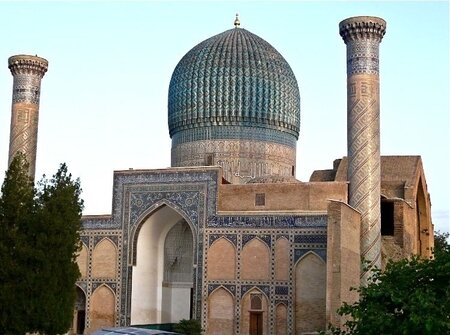

De Mauzolia Tamerlani in Samarkànd. Fotò JC Caraco

★ ★ ★

De Uropi vord balʒàn se de frut tal di històri. Trawàn je staj mol neri a de moderni Persi vord bānjān, je nem in kont tale da usvolpade. Un moz bemarko te od Persi bādemjān id od Arabi bādinjān, in de majsan kaze, solem de pri id de posni silabe prostàj, ba de midi part av meten po vido -er- in Romaniki lingas, -tli-in de vorde odvenan od Turki, id -kla- in Baltislavi vorde, wa usklàr de -l- in Uropi, osmòl maj te di -l- det ja maj neri a de Itali id Greci vorde melanzana id melitzana.

Di storij se u bun ilustrad ov wa se Uropi. De vord balʒàn, uve frontias id de varid lingus form u lingu vig intra tale da polke. Je se os de kaz po de majsan Uropi vorde.

Naturim balʒàn it ne ru tis u komùn Indeuropan rod - je s'anlezi imaʒino Indeuropan nomadi tribe agrizan balʒàne - ba tis seni Persi id Sanskriti, wa se ʒa ne pej. Posim di vord disspanì su u gren part de Indeuropan teritoria (inskluzan India: VZ Hindi bèñgan, versemim od moderni Persi), uveflujan latim su ne-Indeuropan lingas we jegì u pri rola po disspano ja: Arabi id Turki. Befènd, de vorde melanzana in Itali id melitzana in Greci se u bun ilustrad de fenomeni krosen rodis (o micen vordis) we vid os finden in Uropi, wim in liamo = liebe + amo o in fram = friend + ami.

Naturim da vig se ne talvos os vizli be pri viz te, po samp, in écrire, escribir, scrivere, skriva …Ka vizli kovìg ste je intra aubergine id patlıcan (subetàl wan je vid usvoken in de Franci mod "patlikan") ? Pur de esperti oje u linguisti , wim daze un arkeologisti, ve ditego ude u sanditùm de prosàd u veti sitiu. Wim un arkeologìst un ve doʒo gravo u poj po diskrovo de komùn rod usklaran tal, id seto in luc de vadad da rodi tra tem id spas po atelo a de moderni vorde.

Sim se de vige we uniz na: lu se vige celen mol duvim in ni històr id ni kulture. Suplasim nu se tale disemi, tale straniore po unaltem, wim sem so ni lingas: un ve doʒo gravo po diskrovo ni celen unid, we mojse, se ʒe slim de unid humanadi.

★ ★ ★

U Turki plat Imam bayıldı, da se polnen balʒàne. De nom de plati sin "De imam usvanì", par je sì sa bun

★ ★ ★

* Un moz prago sio is de Uzbeki vord vidì inlesten od Rusi, o is de Rusi vord баклажан vidì inlesten od Uzbeki baqlajon*, we som avev viden inlesten od Turki.

★ ★ ★

Une histoire d'aubergines

★ ★ ★

Notre mot français aubergine qui, à première vue, fleure bon le terroir, les marchés de Provence et "l'auberge" de campagne, provient en réalité d'un vieux mot persan bādemjān, lui-même issu du sanskrit vatin-ganah. Bādemjān est passé à l'arabe sous la forme al bādinjān, dans le quel al est l'article, mais qui a été emprunté "en bloc" par le catalan en donnant albergínia, aboutissant en français à notre aubergine. Les Espagnols et les Portugais se sont montrés meilleurs analystes - une fois n'est pas coutume - en séparant le nom de l'article arabe et ont obtenu berenjena et berinjela. La plupart du temps l'article arabe est intégré au substantif espagnol comme dans alcalde (maire) < al qâdī, alcoba (alcôve) < al qúbba, algarabía (charabia) < al arabîya (langue arabe)… Le mot français a connu son heure de gloire auprès des peuples germaniques qui ne connaissaient pas ce légume du soleil, et est passé tel quel en allemand, néerlandais, suédois, danois, norvégien: aubergine, et même en anglais où il concurrence eggplant, produit local, en raison de la forme vaguement ovoïde dudit légume.

On observe en italien un phénomène intéressant que l'on retrouve également en Uropi: celui des racines croisées ou mots métissés. Le mot melanzana provient du croisement du mot arabe bādinjān et du mot italien mela, la pomme. On avait coutume en ces temps anciens de nommer "pomme" tout fruit ou légume nouveau, comme en témoignent pomodoro, la tomate (pomme ou plutôt fruit d'or), le français pomme de terre et le néerlandais aardappel pour désigner ce que les Arawaks appelaient batata et les Espagnols patata. Le terme grec μελιτζάνα "melitzana" est sans doute un emprunt à l'italien, car un croisement avec le mot pomme μήλο "mîlo" aurait plutôt donné "mîlitzana".

★ ★ ★

★ ★ ★

Mais l'histoire de l'aubergine ne s'arrête pas là. Que se passe-t-il dans les Balkans, dominés alors, dans leur quasi-totalité par l'empire Ottoman ? Les Turcs ont eux aussi emprunté le mot arabe bādinjān en le déformant à leur manière: patlıcan (c se prononce [dj] en turc). Il est intéressant de noter au passage que l'azéri, langue altaïque très proche du turc, a emprunté le mot directement au persan: badımcan. Le terme turc a essaimé sur tout le territoire ottoman d'Europe et même au delà: bulgare patladjan, albanais patëllxhan, serbe et croate patlidžan, hongrois padlizsán…

Plus au nord s'étend l'empire des tsars: là aussi, le terme russe баклажан"baklajan" me semble être un emprunt au turc; on le retrouve en biélorusse et ukrainien, mais aussi en polonais: bakłażan, tchèque et slovaque: baklažan, en letton: baklažāns, lituanien: baklažanas, estonien baklažaan et ouzbek baqlajon*.

Le mot persan lui-même bādemjān a subi une évolution interne à l'Iran et aux autres territoires persophones en devenant bānjān qui désigne à la fois la tomate: bānjān e rumi (aubergine de Rome), bānjān e sorkh (aubergine rouge), et l'aubergine: bānjān e siāh, bānjān e sosani.

Restent mystérieux les mots rromani brinʒal et maltais brunġiel. La ressemblance avec bādemjān et ses descendants est assez claire, mais à quelles langues ont-ils été empruntés ?

★ ★ ★

U madrasa (Korani skol) in Bukhara. Fotò JC Caraco

★ ★ ★

Le mot Uropi balʒàn est le fruit de cette histoire. Tout en restant très proche du terme persan moderne bānjān, il tient compte de toutes ces évolutions.On remarquera que du perse bādemjān et de l'arabe bādinjān, dans la plupart des cas, seules les première et dernière syllabes ont survécu: ba/pa et jan/gine. La partie centrale s'est altérée pour devenir -er dans les langues romanes, -tli dans les termes issus du turc, et -kla dans les mots balto-slaves, ce qui justifie le -l- en Uropi, d'autant plus que celui-ci le rapproche du terme italo-grec melanzana / melitzana.

Cette histoire illustre bien ce qu'est l'Uropi. Le mot aubergine, par delà les frontières et les langues diverses constitue un lien linguistique entre tous ces peuples. Il en est de même pour la plupart des mots Uropi.

Bien entendu aubergine ne remonte pas à une racine indo-européenne commune - on imagine mal les tribus indo-européennes nomades cultivant l'aubergine - mais au vieux persan et au sanscrit, ce qui n'est déjà pas si mal. Ce terme s'est ensuite répandu sur une grande partie du territoire indo-européen (y compris l'Inde où le hindi bèñgan semble avoir été emprunté au persan moderne), en débordant largement sur des langues non indo-européennes qui ont joué un rôle essentiel dans sa diffusion: l'arabe et le turc. Enfin, les mots melanzana en italien et melitzana en grec illustrent le phénomène des racines croisées (ou mots métissés) que l'on retrouve également en Uropi, comme dans liamo (aimer) = liebe + amo ou dans fram (ami) = friend + ami.

Naturellement, ce lien n'est pas toujours aussi visible au premier abord que, par exemple, dans écrire, escribir, scrivere, skriva …Quel rapport entre aubergine et patlıcan (surtout lorsque'on le prononce à la française patlikan) ? Il faut l'oeil exercé du linguiste, qui, comme l'archéologue, va détecter la présence d'un site sous un monticule de sable. Comme pour l'archéologue, il va falloir creuser un peu pour remonter à la racine commune qui explique tout, et mettre à jour son cheminement à travers le temps et l'espace pour aboutir aux termes modernes.

Tels sont les liens qui nous unissent: ce sont des liens cachés au plus profond de notre histoire et de nos cultures. En surface, nous sommes tous différents, tous des étrangers les uns aux autres, comme semblent l'être nos langues: il faut creuser pour découvrir notre unité cachée, qui est peut-être - tout simplement - celle de l'humanité.

★ ★ ★

★ ★ ★

Aubergine story

★ ★ ★

The French word aubergine which, at first sight, has a scent of sunny fields, of Provence markets and of country inns ("auberge" = inn in French), in fact stems from an old Persian word bādemjān, itself derived from Sanskrit vatin-ganah. Bādemjāngave Arabic al bādinjān, in which alis the article, but the word was borrowed as a whole in Catalan: albergínia, which in turn gave the French aubergine. Spaniards and Portuguese for once proved to be better analysts, as they separated the Arabic article from the noun, giving berenjena and berinjela. Most of the time in Spanish, the Arabic article is stuck to the noun as in alcalde(mayor) < al qâdī, alcoba (alcove) < al qúbba, algarabía (gibberish) < al arabîya (the Arabic language)… The French word was a great success with Germanic peoples who didn't know that vegetable from sunny climes, and borrowed it as such: aubergine in German, Dutch, Swedish, Danish, Norwegian. It is even used in English in competition with eggplant, a local form, probably due to the vaguely oval shape of the vegetable in question.

In Italian we can observe an interesting phenomenon which can also be found in Uropi: that of crossed roots or portmanteau words. The word melanzana results from the crossing of Arabic bādinjān and Italian mela = apple. In those days people used to call "apple" any new fruit or vegetable, as can be seen in pomodoro = tomato (that is golden apple or rather fruit), in French pomme de terre and Dutch aardappel, to name what Arawaks used to call batata and Spaniards patata, that is potatoe.The Greek word μελιτζάνα "melitzana" was probably borrowed from Italian, because a crossing with the Greek word for apple μήλο"milo" would have rather given "militzana".

But the story of aubergines doesn't stop here. What happened in the Balkan countries, most of which were, at the time, dominated by the Ottoman empire ? The Turks also borrowed the Arabic word bādinjān bending it their own way: patlıcan(c is pronounced j in Turkish). It is interesting to notice in passing that Azeri, an Altaic language very close to Turkish, borrowed the word directly from Persian badımcan. The Turkish term spread all over the Ottoman territory in Europe and even beyond: Bulgarian patladjan, Albanian patëllxhan, Serbian and Croatian patlidžan, Hungarian padlizsán…

Further north lay the Empire of the Tsars: there again, the Russian word баклажан"baklazhan" seems to have been derived from Turkish; it can also be found in Bielorussian and Ukrainian, in Polish: bakłażan, Czech and Slovak: baklažan, in Latvian: baklažāns, Lithuanian: baklažanas, Estonian baklažaan and Uzbek baqlajon*.

The Persian word itself bādemjān, inside Iran and Persian-speaking territories, evolved into bānjān which designates both tomatoes: bānjān e rumi(aubergine from Rome), bānjān e sorkh (red aubergine), and aubergine: bānjān e siāh, bānjān e sosani.

★ ★ ★

U madrasa in Tackent, Uzbekistàn. Fotò JC Caraco

★ ★ ★

Two words remain a mystery: Romani brinʒal and Maltese brunġiel. The likeness with bādemjān and its offspring is clear enough, but what languages were they borrowed from ?

The Uropi word balʒàn is the fruit of this history. While remaining very close to the modern Persan word bānjān, it takes all the various developments into account.It is noticeable that from Persian bādemjān and Arabic bādinjān, in most cases, only the first and last syllables have survived in the other terms: ba/pa and jan/gine. The middle part has changed to become -er in Romance languages, -tli in the terms derived from Turkish, and -kla in Baltic and Slavic words, which accounts for the -l- in Uropi, all the more so as it is closer to the Italian and Greek words melanzana / melitzana.

This story is a good illustration of what Uropi really is. The word aubergine, beyond the frontiers and the diversity of languages forms a language link between all those peoples. This is the case for most Uropi words.

Of course aubergine doesn't go back to a common Indo-European root - you can hardly imagine nomadic Indo-European tribes growing aubergines - yet it goes back to old Persian and Sanskrit, which is not so bad. The word aubergine then spread throughout most of the Indo-European territories (including India where Hindi bèñgan seems to have been borrowed back from modern Persian), and beyond with non Indo-European languages like Arabic and Turkish which played an essential role in its diffusion. Lastly, the words melanzana in Italian and melitzana in Greek are good examples of the portmanteau word (or crossed roots) phenomenon which can also be found in Uropi, for example in liamo(to love) = liebe + amo or in fram (friend) = friend + ami.

Naturally, this link is not always as apparent at first sight as in écrire, escribir, scrivere, skriva …for instance. What can be the connection between aubergine and patlıcan (especially when pronounced in the French way patlikan) ? We need a linguist's trained eye, who, like an archaeologist, will detect a hidden site under a sand mound. As for the archaeologist it is necessary to dig a little to discover the original common root that explains everything, and bring its progression through time and space to light, till we end up with modern terms.

Such are the links binding us together: they are hidden in the depths of our history and our cultures. On the surface, we are all different, all strangers to one another, just like our languages that look so different: you only have to dig a little to discover our hidden unity, which may - quite simply - be that of mankind as a whole.

★ ★ ★

★ ★ ★

* One may wonder whether the Uzbek word was borrowed from Russian, or whether the Russian word баклажан was rather borrowed from Uzbek baqlajon*, which in turn would derive from Turkish.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F2%2F7%2F277026.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F31%2F61%2F321345%2F134515231_o.jpeg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F19%2F44%2F321345%2F134293494_o.jpeg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F01%2F79%2F0%2F134280602_o.jpeg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F42%2F21%2F321345%2F133835185_o.jpeg)