Uropi: U linga we inrìc va - une langue qui vous enrichit - a language that enriches you

* Uropi Nove 95 * Uropi Nove 95 * Uropi Nove 95 *

★ ★ ★

★ ★ ★

Uropi, u linga we inrìc va

★ ★ ★

Soinem ne ! Lero Uropi ve ne deto va gano milione ! Indèt i av uzen de verb inrico id ne arico.

Arico sin deto va ric, ki mole denie. I som, ki Uropi, av ganen mol poj id uspajen ʒe mol.

Inrico, gonim, sin deto va rices kulturim: disvolpo, agreso, inrico vi konade.

Liente ekvos koegle Uropi vorde ki Volapüki vorde. De disemid se anmezi: Volapüki vorde vid nemen od naturi lingas wim Engli, po samp, ba vid disformen po vido adapten a de mol strig fonetiki id gramatiki regle. Po samp nun vord moz fendo ki S, par s se de mark plurali, sim de fendi s in "ros" (= roz, par s in Volapük = [s] id [z]) vid replasen ki L. Odaltia, R esiste ne in Volapük, forsetim par Cine moz ne usvoko R, koslogim de r in "roz" vid os replasen ki L. Sim nu av lol po "roz", wa av nit in komùn ki de odveni vord.

Un dez os te Uropi vorde moz ne vido rekonen anmidim. Di se veri po eki vorde, ne po tale (po samp: ric, linga, vord, naturi, adapto, strig, gramatik, regle, mark, pluràl, esisto, replaso, zi sube se ancepli suprù). Ba Uropi vorde vol diko no de misteric vige esistan intra desade vorde in mole lingas. Uropi vorde se obe u poj misteric id u poj familic.

Po lero Uropi, je sat ne "lero stupim", wim un dez in Franci (apprendre bêtement), un doʒ os incepo (com-prendre); je sat ne lero vorde, je se bunes incepo la, par jaki vord retàl no u storij. Po samp, de verb diko, zi sube. Un moz ne incepo ja suprù, be pri viz, wim je sev de kaz ki "montro" o "mostro". Ba ke ve incepo da vorde ? Francivokore id Italivokore, ba nè un Espàn we dez "encontrar", nè un Englan we dez "show", nè u Dosk we dez "zeigen". Diko, gonim, se no valgim familic, par je det na meno ov "indiquer, indicate, indicar…". Mojse Doske ve ne rekono ja, pur je se puntim de som vord te "zeigen": D av viden Z wim molvos in alten Doski vorde, po s. des = zehn, dant = Zahn, du = zwei… Diko ven od u seni Indeuropan rod *deiḱ-, sinan "diko" we davì de Greci vord, jok uzen odia δείχνω "deikhnô", id os Sanskriti diśati (he dik), Hindi dikhāna, Bengali dēkhānō, Marathi dākhavā (diko), id Latini dico (= dezo). Di rod davì os de vord dig, Latini digitus, de korpipart uzen po diko, we, slogan Merritt Ruhlen se un od hi 27 moldi rode (tik). In Germàni lingas, je davì os Doski Zeichen, Nd teken, Da, Nor tegn, Sw tecken, Eng token = sig.

★ ★ ★

★ ★ ★

Sim, leran "diko", un ler ne solem un Uropi vord, ba un ler os de storij de vordi, un diskròv bemìn 19 kogenen vorde in 19 disemi lingas. Lero, diskrovo, incepo… o priʒe diskrovo, incepo, lero. Lero Uropi se wim liso u bib in wen un usploror retàl hi diskrovade in dali lande, ki misteric polke vokan strani lingas. Indèt i av usploren eke 40 veti id moderni Indeuropan lingas, id alten lingas we, tra suntjàre, avì intrametade ki la wim Fini-Ugri lingas po samp, id intra la i av finden - (mole linguiste avì deten ja for ma) - suntade vige po ne dezo tiliade, ekvos de maj strani vige. Po samp de vord has, we ven od de Germàni vorde Haus, house, huis, hus, id be som tem od de Romaniki vorde casa, casă, koruvòk puntim a de Hungàri vord ház, obte Hungàri se nun Indeuropan linga. Od ko ven di vord ? Vidì je inlesten ?

Da "misteric vige" moz so deben a u komùn erdad (de komùn Indeuropan rode), a inleste, po samp od Latini id Greci, a usfali kogonade o a anzaven kogenade: stì je ne u mol veti kogenad intra Indeuropan id Urali-Altaji lingas (de simnomen Nostrati hipotèz) ?

Ba nemem alten sampe.

De verb koeglo: je s'anmozli rekono ja suprù, wim is un avev "komparo"; un doʒ analìzo ja: de prefìks ko- = ki, sam, id egli. "Egli" av u dupli odvenad: Romaniki, od Latini æqualis we davì It. uguale, Esp igual, Fr. égal…, usklaran de eg-l id Germàni, od Doski gleich, Nd gelijk, Da lig, Sw lika, No lik, usklaran de -gli. Sim koeglo (ko + egli) vid struen puntim wim Latini comparo (cum = ki + par = egli), ba je vid os struen wim de Balti id Slavi vorde: Latvi: sa-līdzināt (sa- = ko-, līdzīgs = egli), Rusi s-ravnit' (s- = ko-, ravnyï = egli), Tceki s-rovnávat, Kro s-ravniti, Bul s-ravniavam…

★ ★ ★

Anmidim.

De Franci id Engli vorde "immédiat" id "immediate" vid leren ane vido analizen par nu se siuden a Romaniki lingas. Ba wan nu vol lero Germàni, Slavi lingas o Greci, je se no nudi analìzo de vorde, altem nu incepev nit, id da lingas sev tio anlezi a lero.

De Doski vord se unmittelbar: -bar se un adjetivi fendad; un av "Mittel" = mid, be mid, id un- we se de adjetivi negad = an-. Di adjetìv sin direkti, ane intramid, sim suprù, anmidi, puntim de sin de vordis "immédiat, immediate", od Latini in- = an- id medius = midi. Uzem num ni analìz in alten lingas: Nizilandi: on-middel-lijk, Dani, Norveji: u-middel-bar, Swedi: o-medel-bar id os in Greci: a-mesos (a- = an- + mesos = midi), in Armèni an-midʒak-an (midʒak = midan)… Sim de Uropi vord anmidi(m) moj ne so rekonli be pri viz, ba wan un av analizen ja, un moz incepo de som vord in 14 alten lingas, wa sin ne te nu av leren da lingas naturim, ba te lu se no nemaj kopolem straniori, id mojse… nu ve avo de zel lero la.

Usvoko

Je ven od voko, we esìst in nun Europan linga ki da sinad. Je ven od u veti Indeuropan rod *wekw- = voko, we davì Latini voco = calo, vox (voc), id os Greci epos (vord), eipon (vokì), novi Gr eipa (dezì). Un find ja os in Sanskriti vákti (he vok), vacas- (vok, vokad), vāk (voc, vok), Hindi vaktā (vokor), vachan (vok), vākya (fraz); je davì os mole vorde in moderni Europan lingas: voc (= voce, voz, voix, voice…), vokàl (= Vokal, vokál, vowel, voyelle…), voci (= vocal, vokalisch, vokal'nyï, vokalni…), vokabular (= vocabulaire, vocabolario, vocabulari, vocabular, vocabulary, Vokabular, vokabular…), id Gaeli focal (= vok, vord), focloir (= vordar), avokàt…

De kosetad us + voko vid finden insemli struade in mole lingas: Doski: aus-sprechen (sprechen = voko), Nd uit-spreken, Da ud-tale (tale = voko), Nor ut-tale, Swe ut-tala, id os Kroati, Serbi, Slovèni iz-govoriti (govoriti = voko), Tceki vy-slovit, Slovaki vy-slovit', Polski wy-mawiać, Latvi iz-runāt, Lituvi iš-tarti… In tale da lingas, de prefìks sin "us" id de verb "voko" o "dezo".

★ ★ ★

Muzikor in Jodhpur, India

★ ★ ★

Prijan

De rod prij- we av daven prijo, prijan, prijad, prijim id de usprès Prijen akono va !, ven od u veti Indeuropan rod *prihx-eha- sinan "liamo", we davì Sanskriti priya = keri, liamen, fram, liamor, prīyate = prijo, davo prijad, liamo, prīnana = prijan, prīti = glajad, satizad, liam, Hindi priye = keri, prīti, prem = liam, premī = liamor, premika = liamora, Bengali, Gudʒarati, Marathi priya = keri. Je davì os mole vorde in Slavi id Germàni lingas: Rusi prijatnyj, Serbi prijatan, Slovèni prijeten, Bul prijaten, Tceki příjemný, Polski przyjemny = prijan, Kroati, Slovèni prijatelj, Bul prijatel, Tce přítel, Slovaki priatel', Pol przyjaciel = fram, id os Latvi prieks = glajad.. In Germàni lingas, prij- vid fri- wim in Eng friend, Do Freund, Nd vriend = fram, Do Friede, Nd vrede, Swe, Da, Nor fred = pac, Do frei, Eng free, Nd vrij, Swe, Da, nor fri = lifri.

Di se eke rode we s'ne Latini, ba pur se mol intranasioni.

Del, prodèl

De vord del ven od Rusi delo = del, od de verb delat' = deto. De vig intra del id deto se klar: un find ja os in Franci intra faire id af-faire, o in Itali intra fare id af-fare (= deto, del). Ba del ven os od de Engli vord deal we sin "tradèl, del, kontràt" id de verb to deal with sin "sia benemo ov, treto, delo ov…". De kest Ov ka del je ? koruvòk a Rusi v tciom delo ? (Lit. "in ka (se) de del?"). Rusi delo, delat' ven od de Indeuropan rod *dheh1- we sinì odvenim "seto, plaso", wim in novi Greci thetô id Lituvi dėti; ba dapòs je nemì os de sin "deto", wim in Latini facio, Engli do, Nd doen, Do tun, Rus delat', Tce dělat, Slo delati id Uropi deto. Engli deal, gonim ven od de I-E rod *dail-, discizo, disparto, we davì os Do Teil, Nd deel, Da, Swe, Nor del = "part". Del dav no de vord prodèl (de del we det va ito pro, pro-vado), wen un find os ki de som sin in Norveji, Dani for-del (lit. pro-part), Swe för-del, Nd voor-deel, Do Vor-teil. Rudèl, gonim se de del, de zoc we det va ruvado o rustajo (vz Do Nachteil, Nd nadeel, Swe nackdel).

★ ★ ★

Plaz Navona, Roma, Italia

★ ★ ★

Alten struen Uropi vorde se relativim lezi a incepo be pri viz. Po samp: versemi (we sem veri), wim Latini verisimilis, Esp verosímil, It verosimile, Fr vraisemblable, Rum verosimil, Do wahrscheinlich, Nd waarschijnlijk… o uspajo, da se "pajo us, davo denie usia, a ekun alten".

Sim je se klar te, lero id analizo Uropi vorde ne solem dav no u menti gimnastik, mol uzi po lero aktivim straniori lingas, ba je pomòz no diskrovo mole zoce ov mole lingas, un diskròv de misteric vige esistan intra de vorde numari Indeuropan lingas, sim un moz dezo te Uropi "kreàt u vig intra lingas", wim dez ni mota "Kreato u vig intra polke". Naturim un moz ʒe os lero Uropi "stupim", ane prago sio keste, ba i se kovikten te de misteric aspèk eki Uropi vordis - we vid ne rekonen be pri viz - ve andubim veko vi gurnovid, ve inproso va prago vo "Parkà ?", ve duto va a diskrovo de komùn històr Uropi id alten Indeuropan vordis.

In mi menad, tal wim po naturi lingas, de struad un Intranasioni Eldilingu doʒ so diakronic id sinkronic, da se je doʒ vido bazen su de històr de vokabulari id sintaksi, id su de ustensad li geografic uzadi tra lingas. Un moz ne so satizen, po samp, ki un insanim Romaniki leksik, oʒe is je vid sprajen zi id za ki eke inleste od Cini-Tibeti, Semiti, Urali-Altaji, o Bantù.

Vize os:

http://uropi.canalblog.com/archives/2013/11/07/28380100.html

http://uropi.canalblog.com/archives/2013/11/10/28401660.html

★ ★ ★

Uropi, une langue qui vous enrichit

★ ★ ★

Ne rêvons pas ! Ce n'est pas en apprenant l'Uropi que vous gagnerez des millions ! D'ailleurs, j'ai employé en Uropi le verbe inrico plutôt qu'arico.

Arico signifie "rendre riche", faire gagner de l'argent. Avec l'Uropi, j'ai gagné très peu et dépensé beaucoup.

Inrico, au contraire, c'est s'enrichir intellectuellement, culturellement, développer, enrichir ses connaissances.

Certains comparent parfois les mots Uropi au Volapük; la différence est immense. Les mots Volapük sont empruntés à des langues naturelles comme l'anglais, mais ils ont été déformés pour les adapter aux règles très strictes de la phonétique et de la grammaire de la langue. Par exemple, aucun mot ne peut se terminer par S qui est la marque du pluriel, si bien que le s final dans "ros" (rose = Uropi roz, mais le s Volapük sert pour S et Z), est remplacé par L. Par ailleurs le R n'existe pas en Volapük car les Chinois sont supposés ne pas pouvoir le prononcer; le r de [roz] est donc lui aussi remplacé par L. Nous aboutissons donc à lol pour la rose, ce qui n'a plus rien à voir avec le [roz] d'origine.

On nous dit aussi que les mots Uropi ne se reconnaissent pas au premier coup d'oeil. C'est parfois vrai, bien que ce ne soit pas le cas pour tous (par exemple: ric, linga, vord, naturi, adapto, strig, gramatik, regle, mark, pluràl, esisto, replaso, se comprennent immédiatement). Cependant, on dirait que certains mots Uropi sont là pour nous initier aux liens mystérieux qui existent entre des dizaines de mots appartenant à de nombreuses langues. Les mots Uropi sont à la fois mystérieux et familiers.

Pour apprendre l'Uropi, il ne nous suffit pas "d'apprendre bêtement", comme on dit en français; il nous faut aussi comprendre: apprendre seul n'est pas satisfaisant, mieux vaut chercher à comprendre, car chaque mot nous raconte une histoire. Prenons par exemple le verbe diko = montrer: on n'en saisit pas immédiatement le sens comme ce serait le cas avec "montro" ou "mostro". Mais qui peut reconnaître ces derniers termes ? Un Français et un Italien, mais pas un Espagnol qui dit "encontrar", ni un Anglais qui dit "show", ni un Allemand qui dit "zeigen". Diko, en revanche, nous est vaguement familier, car il nous fait penser à indiquer, indicate, indicar, indicare… Peut être que les Allemands n'y reconnaîtront pas le verbe zeigen qui est pourtant exactement le même mot: D est devenu Z comme souvent en allemand: dix = zehn, dent = Zahn, deux = zwei. Diko vient d'une vieille racine indo-européenne *deiḱ- = montrer, qui a donné le grec moderne δείχνω "deikhnô" (montrer), ainsi que le sanskrit diśati (il montre), le hindi dikhāna, le bengali dēkhānō, le marathe dākhavā (= montrer), et le latin dico (= dire). Cette racine a également donné le mot doigt, latin digitus, la partie du corps qui sert à montrer, et selon Merritt Ruhlen il s'agit là d'une de ses 27 racines mondiales: (tik). Dans les langues germaniques, elle a donné, en dehors de zeigen, l'allemand Zeichen, Nd teken, da, nor tegn, sué tecken, Eng token = signe.

★ ★ ★

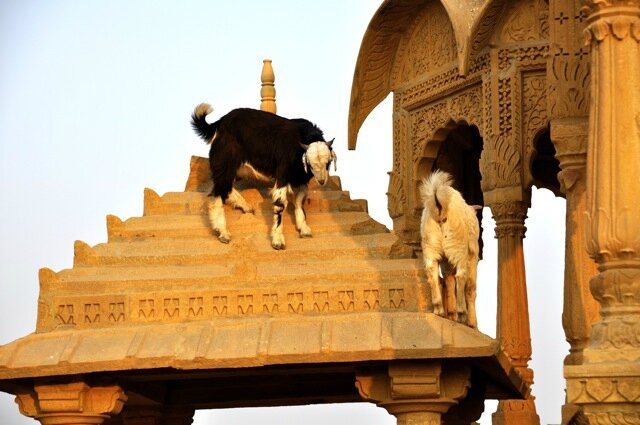

Kadas su de tag u kenotafi, Jaisalmer, India

★ ★ ★

C'est ainsi qu'en apprenant diko, on n'apprend pas seulement un mot Uropi, mais on découvre aussi l'histoire de ce mot, on rencontre au moins 19 autres termes apparentés dans 19 langues différentes. On apprend, on découvre, on comprend… ou plutôt, on découvre, on comprend, on apprend. Apprendre l'Uropi, c'est comme ouvrir le livre d'un explorateur qui fait le récit de ses découvertes dans des pays lointains, de ses rencontres avec des peuples mystérieux qui parlent des langues étranges. J'ai véritablement exploré une quarantaine de langues indo-européennes anciennes et modernes, ainsi que d'autres langues qui ont pu, au cours des siècles, avoir des échanges avec elles, comme les langues finno-ougriennes, par exemple, et entre elles, j'ai découvert (comme bien d'autres l'avaient fait avant moi), des centaines de liens, pour ne pas dire des milliers, parfois des liens des plus étranges. Par exemple, le mot Uropi has = maison, qui vient des termes germaniques: Haus, house, huis, hus, et en même temps des termes romans: casa, casă, correspond exactement au mot hongrois ház = maison, bien que le hongrois ne soit pas une langue indo-européenne. Doù vient ce mot hongrois ? Est-ce un emprunt ?

Ces "liens mystérieux" peuvent être dûs à un héritage commun (les racines indo-européennes), à des emprunts, au grec ou au latin par exemple, à des rencontres fortuites ou à des parentés encore inexplorées: n'y a-t-il pas eu une parenté très ancienne entre les langues indo-européennes et ouralo-altaïques ? (la fameuse hypothèse nostratique).

Mais prenons d'autres exemples:

Le verbe koeglo (comparer): impossible de le reconnaître immédiatement comme si nous avions "komparo"; il faut l'analyser: le préfixe ko- (avec, ensemble = con-, com-, co-) et egli = égal. Egli a une double origine: romane, du latin æqualis qui a donné: égal, it uguale, esp igual…, (ce qui explique le eg-l) et germanique, de l'allemand gleich, Nd gelijk, da lig, sué lika, nor lik, (ce qui explique le -gli). Ainsi koeglo (ko +egli) se construit exactement comme le latin comparo (cum = avec + par = égal), mais également comme ses équivalents dans les langues baltes et slaves: letton: sa-līdzināt (sa- = com-, līdzīgs = égal), russe s-ravnit' (s- = com-, ravnyï = égal), Czech s-rovnávat, cro s-ravniti, bul s-ravniavam…

★ ★ ★

★ ★ ★

Anmidim = immédiatement.

On apprend les mots French et anglais "immédiat" et "immediate" sans les analyser, car nous sommes habitués aux langues romanes. Mais lorsque nous voulons étudier une langue germanique ou slave ou le grec, il nous faut analyser les mots, sinon, on n'y comprend rien, et l'apprentissage de ces langues devient trop difficile.

Le terme allemand: unmittelbar s'analyse en -bar, terminaison adjectivale, "Mittel" = milieu, au milieu, et un- négation de l'adjectif = in-, im-. Cet adjectif signifie direct, sans intermédiaire, donc tout de suite, immédiat, ce qui est la signification exacte des mots "im-médiat, im-mediate", du latin in- et medius = du milieu. Utilisons maintenant cette analyse dans d'autres langues: en néerlandais on-middel-lijk, danois, norvégien: u-middel-bar, suédois: o-medel-bar, ainsi qu'en grec: a-mesos (a- = im- + mesos = du milieu), en arménien an-midjak-an (midjak = moyen, du milieu). Le mot Uropi anmidi(m) peut très bien ne pas être reconnaissable de prime abord, mais lorsqu'on l'a analysé, il nous permet de comprendre ses équivalents dans 14 langues. Ceci ne signifie pas, bien sûr, que nous aurons appris ces langues, mais qu'elles ne nous seront plus totalement "étrangères", et que peut être… nous aurons envie de les apprendre.

Usvoko = prononcer.

Ce mot vient de voko (parler) qui n'existe dans aucune langue européenne moderne avec ce sens là. Il s'agit d'une vieille racine indo-européenne: *wekw- = parler, que l'on retrouve dans le latin voco = appeler, vox (voix), et aussi dans le grec epos (parole), eipon (ont parlé), gr.mod eipa (j'ai dit). On la retrouve également en sanskrit vákti (il parle), vacas- (parole, discours), vāk (voix, parole), en hindi vaktā (orateur), vachan (voix), vākya (phrase), et dans de nombreux termes existant dans des langues européennes modernes: la voix (= voce, voz, voice…), la voyelle (= Vokal, vokál, vowel…), vocal (= vokalisch, vokal'nyï, vokalni…), vocabulaire (= vocabolario, vocabulari, vocabular, vocabulary, Vokabular, vokabular…), dans les mots irlandais focal (= mot, parole), focloir (= dictionnaire), avocat…etc.

La construction us (ex-, hors de) + voko pour "prononcer", se retrouve dans de nombreuses langues: allemand: aus-sprechen (sprechen = parler), Nd uit-spreken, da ud-tale (tale = parler), nor ut-tale, sué ut-tala, ainsi qu'en croate serbe, slovène iz-govoriti (govoriti = parler), en tchèque vy-slovit (slovo = parole), slovaque vy-slovit', Polish wy-mawiać, letton iz-runāt, lituanien iš-tarti… Dans toutes ces langues le préfìxe signifie "ex-" et le verbe "parler" ou "dire".

★ ★ ★

Kastèl Sant Angelo, Roma, Italia

★ ★ ★

Prijan = agréable

La racine prij- qui a donné prijo, prijan, prijad, prijim (plaire, agréable, plaisir, s'il vous plaît) et l'expression Prijen akono va (enchanté de faire votre connaissance) vient de la vieille racine indo-européenne *prihx-eha- qui signifie "aimer". On la retrouve dans le sanskrit priya = cher, aimé, ami, amant, prīyate = plaire, faire plaisir, aimer, prīnana = agréable, prīti = joie, satisfaction, amour, le hindi priye = cher, prīti, prem = amour, premī = amant, premika = amante, le bengali, goudjarati, marathe priya = cher. Elle a donné également de nombreux termes dans les langues slaves et germaniques: russe priyatnyï, serbe prijatan, slovène prijeten, bul prijaten, tchèque příjemný, polonais przyjemny = agréable, croate, slovène prijatelj, bul prijatel, tche přítel, slk priatel', pol przyjaciel = ami, ainsi que le letton prieks = joie. Dans les langues germaniques, prij- devient fri- comme dans l'ang friend, l'al. Freund, le Nd vriend = ami, al. Friede, Nd vrede, sué, da, nor fred = paix, al. frei, ang free, Nd vrij, sué, da, nor fri = libre.

Ce sont là quelques racines, qui, pour ne pas être latines n'en sont pas moins très internationales.

Del, prodèl = affaire, avantage

Le mot del vient du russe delo = affaire, du verbe delat' = faire. Le lien entre ces deux termes est clair: on le retrouve en français entre faire et af-faire, et en italien entre fare et af-fare. Mais del vient aussi de l'anglais deal qui signifie "transaction, affaire, contrat" et du verbe to deal with qui signifie "s'occuper de, traiter…". La question Ov ka del je ? (de quoi s'agit-il ?) correspond au russe v tchiom delo ? (lit. "en quoi (est) l'affaire?"). Les mots russes delo, delat' viennent de la racine indo-européenne *dheh1- qui signifie à l'origine "mettre, placer", comme en grec moderne thetô et en lituanien dėti; mais par la suite, cette racine a pu prendre le sens de "faire", comme en latin facio, anglais do, Nd doen, al tun, rus delat', tch dělat, slo delati et en Uropi deto. L'anglais deal, en revanche, vient de la racine i-e *dail-, diviser, partager, que l'on retrouve en al Teil, Nd deel, da, sué, nor del = "partie". Del nous donne en Uropi prodèl (= avantage: pro- = devant: l'affaire, la chose qui nous fait avan-cer), exactement comme en norvégien, et danois for-del (lit. avant + partie, chose), Sué för-del, Nd voor-deel, al Vor-teil. Rudèl (inconvénient), au contraire, c'est l'affaire, la chose qui nous fait reculer (= ru-vado, de ru- = en arrière) ou rester en arrière (ru-stajo), (cf al Nachteil, Nd nadeel, sué nackdel = inconvénient).

★ ★ ★

Ʒina ki beb, Jodhpur, India

★ ★ ★

D'autres termes Uropi construits sont relativement faciles à comprendre du premier regard, par exemple versemi (qui semble semo, vrai veri) comme dans le latin verisimilis, esp verosímil, it verosimile, fr vraisemblable, roum verosimil, al wahrscheinlich, Nd waarschijnlijk… ou bien uspajo, c'est à dire "payer (pajo) en dehors (us)", donner de l'argent à l'extérieur, c'est à dire "dépenser".

Il est donc clair qu'apprendre et analyser les mots Uropi nous donne non seulement une gymastique d'esprit très utile pour aborder de façon active les langues étrangères, mais nous permet de découvrir beaucoup de choses dans de nombreuses langues. On découvre les liens mystérieux qui existent entre les mots des différentes langues indo-européennes, si bien qu'on peut dire que l'Uropi "crée un lien entre les langues", comme le dit notre devise: "Créer un lien entre les peuples". Bien sûr, on peut aussi apprendre l'Uropi "bêtement", si l'on veut, sans se poser de questions, sans "se prendre la tête", comme on dit aujourd'hui, mais je suis convaincu que le côté mystérieux de nombreux mots de cette langue ne manquera pas de susciter notre curiosité, de nous inciter à nous demander "Pourquoi ?", et par là même nous emmener à la découverte de notre histoire linguistique commune, celle de l'Uropi et des autres langues indo-européennes.

A mon sens, à l'image des langues naturelles, la construction d'une LAI doit être diachronique et synchronique, c'est à dire se baser à la fois sur l'histoire du lexique et de la syntaxe et sur leur extension géographique à travers les langues. Je reste persuadé qu'on ne peut pas se contenter, par exemple d'un lexique purement latin, même s'il est saupoudré ça et là de quelques emprunts au sino-tibétain, aux langues sémitiques, ouralo-altaïques ou bantoues.

Voir aussi:

http://uropi.canalblog.com/archives/2013/11/07/28380100.html

http://uropi.canalblog.com/archives/2013/11/10/28401660.html

★ ★ ★

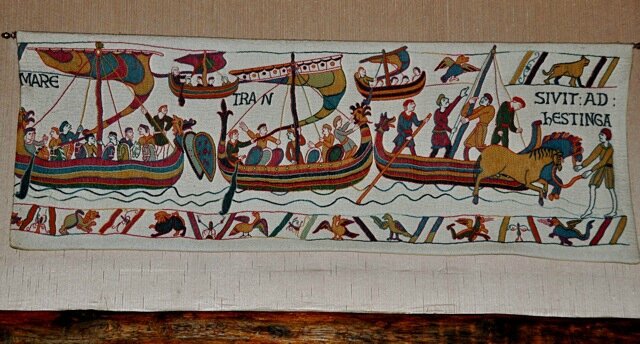

Wilem de Kovaldor id hi trupe usbarkan in Hasting, pos u tapiserij in Bayeux, Francia

★ ★ ★

Uropi, a language that enriches you

★ ★ ★

Let's not imagine things ! Learning Uropi won't make you rich ! Indeed I've used the Uropi verb inrico rather than arico.

Arico means "make you rich", enable you to make money. With Uropi, I earned very little and spent a lot.

Inrico, on the other hand, means enriching your culture, your experience, your knowledge.

People sometimes compare Uropi words to Volapük: there is an enormous différence. Volapük words were borrowed from natural languages like English, but they were distorted so that they might comply with the very strict phonetic and grammatical rules of the language. For instance, no word can end with S because it is the plural mark, so that the final s in "ros" (rose = Uropi roz, but Volapük uses s for S and Z), is replaced with L. Besides, R doesn't exist in Volapük because the Chinese are not supposed to be able to pronounce it; so the r in [roz] is also replaced with an L. Thus we end up with lol for "rose", which has nothing to do with the original word.

Some others also say that Uropi words cannot be recognized at first sight. This is sometimes true, although it isn't always the case (for example: ric, linga, vord, naturi, adapto, strig, gramatik, regle, mark, pluràl, esisto, replaso, can be understood immediately). However, some Uropi words seem to be wishing to acquaint us with the mysterious links existing between dozens of terms belonging to many different languages. Uropi words are both slightly mysterious and relatively familiar.

To learn Uropi, it is not enough to "learn stupidly", as the French say; we also need to understand: learning alone is not satisfactory, trying to understand is much better, for each word tells us a story. Let's take the verb diko (to show), for example: you cannot understand it immediately as would be the case with "montro" or "mostro". But who can recognize the latter terms ? French people or Italians, but neither Spaniards who say "encontrar", nor English speakers who say "show", nor Germans who say "zeigen". Diko, on the other hand, is vaguely familiar to us, because it makes us think of indicate, indiquer, indicar, indicare… May be Germans won't recognize the verb zeigen though it is exactly the same word: D has become Z as often in German: decem, dix, diez = zehn, dent = Zahn, due = zwei. Diko stems from an old Indo-European root *deiḱ- (to show), which gave modern Greek δείχνω "deikhnô" (to show), as well as Sanskrit diśati (he shows), Hindi dikhāna, Bengali dēkhānō, Marathi dākhavā (to show), and Latin dico (to say). This root also gave birth to the word finger, in Latin digitus, the part of the body we use to show, and, according to Merritt Ruhlen it is one of his 27 world roots: (tik). In Germanic languages, apart from zeigen, it also gave birth to German Zeichen, Dutch teken, Da, Nor tegn, Swe tecken, Eng token = sign.

★ ★ ★

Jun dansora in de Thar vustia, India

★ ★ ★

Therefore, learning diko, you do not only learn one Uropi word, but you also discover the story of this word, you meet at least 19 other cognates in 19 different languages. You learn, you discover, you understand… or rather, you discover, you understand, you learn. Learning Uropi, is like reading an explorer's book telling the story of his discoveries in faraway countries, where he meets mysterious populations speaking strange languages. I have indeed explored some forty ancient and modern Indo-European languages, as well as other languages which could, over the centuries, have had exchanges with them, like Finno-Ugric languages, for example, and among them, I discovered (as many linguists did before me), hundreds of links, not to say thousands, and sometimes the strangest links. For example, the Uropi word has (house), that comes from Germanic: Haus, house, huis, hus, and at the same time form Romance: casa, casă, corresponds exactly to Hungarian ház (house), although Hungarian is not an Indo-European language. Where does this Hungarian word come from ? Is it a loan word ?

Those "mysterious links" may be due to a common heritage (Indo-European roots), to borrowings from Greek or Latin for instance, to casual encounters or still undiscovered kinships: isn't there an extremely old relationship between Indo-European and Ural-Altaic languages ? (the famous nostratic hypothesis).

But let us take other examples:

The verb koeglo (compare): it is impossible to recognize it immediately as would be the case for "komparo"; you have to analyse it: prefix ko- (with, together = con-, com-, co-) and egli (equal). Egli has a double origin: Romance, from Latin æqualis that gave Fr égal, It uguale, Sp igual, Eng equal …, (which account for the eg-l) and Germanic, from German gleich, Dutch gelijk, Da lig, Swe lika, Nor lik, (which account for the -gli). Thus, koeglo (ko + egli) is exactly built like Latin comparo (cum = with + par = equal), but also like its equivalents in Baltic and Slavic languages: Latvian: sa-līdzināt (sa- = com-, līdzīgs = equal), Russian s-ravnit' (s- = com-, ravniy = equal), Czech s-rovnávat, Cro s-ravniti, Bul s-ravniavam…

★ ★ ★

Anmidim = immediately.

We learn the French and English "immédiat" and "immediate" without analysing them, because we are used to Romance languages. But when we want to study a Germanic or Slavic language or Greek, we need to analyse the words, otherwise we cannot understand anything, and learning those languages becomes too difficult.

The German word: unmittelbar can be analysed as follows: -bar, adjective ending, "Mittel" = middle, in the middle, and un- negative prefix = un-, in-, im-. This adjective means direct, without intermediary, therefore instant, immediate, which is the precise meaning of the words "im-médiat, im-mediate", from Latin in- and medius = middle. Let us now use this analysis in other languages: in Dutch on-middel-lijk, Norwegian and Danish: u-middel-bar, Swedish: o-medel-bar, as well as in Greek: a-mesos (a- = im- + mesos = middle), in Armenian an-mijak-an (mijak = average, middle). The Uropi word anmidi(m) may well not be recognized at first sight, but once you have analysed it, it enables you to understand its equivalents in 14 languages. This doesn't mean, of course, that you have learnt those languages, but that they will no longer be totally "foreign" to you, and that … you may feel like learning them.

Usvoko = to pronounce.

This word comes from voko (to speak) which exists in no modern European language with this meaning. It stems from an old Indo-European root: *wekw- (to speak), that we can find in Latin voco (to call), vox (voice), and also in Greek epos (word), eipon (they spoke), mod.Gr. eipa (I said). It can also be found in Sanskrit vákti (he speaks), vacas- (word, speech), vāk (voice, word), in Hindi vaktā speaker), vachan (voice), vākya (sentence), and in numerous words in modern European languages: voice (= voce, voz, voix…), vowel (= Vokal, vokál, voyelle…), vocal (= vokalisch, vokal'nyï, vokalni…), vocabulary (= vocabolario, vocabulari, vocabular, vocabulaire, Vokabular, vokabular…), in the Irish words focal (word), focloir (= dictionary), advocate…, etc.

The construction us (out) + voko (speak) for "pronounce" can be found in numerous languages: German: aus-sprechen (sprechen = speak), Dutch uit-spreken, Da ud-tale (tale = speak), Nor ut-tale, Swe ut-tala, as well as in Croatian, Serbian, Slovene iz-govoriti (govoriti = speak), in Czech vy-slovit (slovo = word), Slovak vy-slovit', Polish wy-mawiać, Latvian iz-runāt, Lithuanian iš-tarti… In all these languages the prefìx means "out-" and the verb "to speak" or "to say".

★ ★ ★

Venezan mask, Italia

★ ★ ★

Prijan = pleasant

The root prij- which has given prijo, prijan, prijad, prijim (to please, pleasant, pleasure, please) and the phrase Prijen akono va (pleased to meet you) stems from the old Indo-European root *prihx-eha- meaning "to love, to like". It can be found in Sanskrit priya = dear, beloved, friend, lover, prīyate = to please, satisfy, love, prīnana = pleasant, prīti = joy, satisfaction, love, in Hindi priye = dear, prīti, prem = love, premī = lover (man), premika = lover (woman), in Bengali, Gujarati, Marathi priya = dear. It also gave numerous terms in Slavic and Germanic languages: Russian priyatniy, Serbian prijatan, Slovene prijeten, Bul prijaten, Czech příjemný, Polish przyjemny = pleasant, Croatian, Slovene prijatelj, Bul prijatel, Cze přítel, Slk priatel', Pol przyjaciel = friend, as well as Latvian prieks = joy. In Germanic languages, prij- becomes fri- as in Eng friend, Ger Freund, Dutch vriend, Ger Friede, Dutch vrede, Swe, Da, Nor fred = peace, Ger frei, Eng free, Dutch vrij, Swe, Da, Nor fri.

These are a few root-words, which may not be Latin or Romance but are very international all the same.

Del, prodèl = business, advantage

The word del comes from Russian delo = business, deal, from the verb delat' = to do. The link between these two terms is perfectly clear: you can find it in French between faire and af-faire, and in Italian between fare and af-fare. But del also comes from English deal meaning "transaction, business, contract" and from the verb to deal with. The Uropi question Ov ka del je ? (What's up ? What is it about ?) corresponds to Russian v chyom delo ? (lit. "in what (is) the matter ?"). Those Russian terms delo, delat' stem from the Indo-European root *dheh1- which meant "to put, to place" originally, as in modern Greek thetô and in Lithuanian dėti; but later on, also came to mean "to do", as in Latin facio, English do, Dutch doen, Ger tun, Rus delat', Cze dělat, Slo delati and in Uropi deto. The English word deal, on the other hand, stems from the I-E root *dail-, to divide, to share, that can be found in Ger Teil, Dutch deel, Da, Swe, Nor del = "part". In Uropi Del has given prodèl (= advantage: from pro- = forward, in front: the thing that makes us advance, move forward, pro-gress), exactly as in Norwegien, and Danish for-del (lit before (forward) + part), Swe för-del, Dutch voor-deel, Ger Vor-teil. Rudèl (drawback), on the contrary, is the thing that makes you move back (= ru-vado, from ru- = back) or stay behind (ru-stajo), (cf Ger Nachteil, Dutch nadeel, Swe nackdel = drawback).

★ ★ ★

U noria in India

★ ★ ★

Other Uropi terms that were built similarly are relatively easy to understand at first sight, for example versemi (that seems semo, true veri = likely, plausible) as in Latin verisimilis, Sp verosímil, It verosimile, Fr vraisemblable, Rom verosimil, (cf verisimilitude), Ger wahrscheinlich, Dutch waarschijnlijk… or uspajo lit. "to pay out", that is "to spend".

Therefore it is quite clear that learning and analysing Uropi words not only gives you the mental gymnastics that is most useful to learn foreign languages actively, but also enables you to discover many things in numerous languages. You can discover the mysterious links existing between the words of the different Indo-European languages, so we can say that Uropi "creates a link between languages", as the Uropi motto says "To create a link between the peoples". Of course, you can also learn Uropi "stupidly", if you like, without asking yourselves any questions, but I am convinced that the mysterious side of many words in the language will inevitably arouse your curiosity, will incite you to ask "Why is that so?", and thus will take you off to explore the our common linguistic history, that of Uropi and the other Indo-European languages.

I think that, similarly to what happened naturally in our languages, constructing an IAL should be both diachronic and synchronic, i.e it should be based on the history of the vocabulary and syntax, as well as their geographical extension through languages. I am convinced that we cannot be content with a purely Romance vocabulary, for instance, even if it has been sprinkled with a few loan words from Sino-Tibetan, from Semitic, Ural-Altaic or Bantu languages.

See also:

http://uropi.canalblog.com/archives/2013/11/07/28380100.html

http://uropi.canalblog.com/archives/2013/11/10/28401660.html

★ ★ ★

Almuñécar, Andalusia, Espania

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F2%2F7%2F277026.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F42%2F21%2F321345%2F133835185_o.jpeg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F60%2F50%2F321345%2F131836320_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F73%2F77%2F321345%2F130540623_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F46%2F98%2F321345%2F129165442_o.jpg)