Uropi: Ov Engli, Hindi id alten lingas - Anglais, hindi et autres langues - English, Hindi and other languages

★ ★ ★

* Uropi Nove 54 * Uropi Nove 54 * Uropi Nove 54 *

★ ★ ★

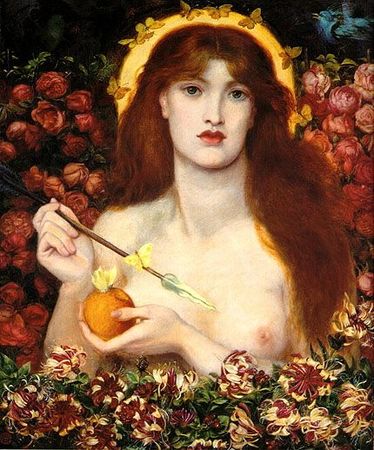

Pre-Rafaeliti picten

* * *

Ov Engli, Hindi id alten lingas

* * *

Probleme traskrivadi

I find te Engli se ne bun adapten po traskrivo alten lingas.

Usvòk

De pri anlezid, wan un vol traskrivo ki Engli u linga ne uzan Latini tipe, ven od de Engli usvòk. Engli, koeglen ki de majsan alten Europan lingas, av mol partikuli vokali zone. Idmàj, jaki skriven vokàl o grup vokalis av ne un, ba vari disemi usvoke.

Po samp a moz vido usvoken [ə] wim in de artikel a = u, [ei] wim in cake, [ā:] wim in car, [ō:] wim in all, [æ] wim in cat; e moz vido usvoken [e] wim in bed, [ī:] wim in evening, ekvos [i] wim in women, chicken, i.s.p., i moz vido usvoken [i] wim in pig, [ai] wim in life…, o moz vido usvoken [o] wim in not, [əu] wim in nose… u moz vido usvoken [∧] wim in cut, [jū:] wim in tube, ekvos [ū:] wim in sure.

Nu av de som problèm ki vokaligrupe id diftonge: oo vid usvoken [u], kurti u, wim in book, o [ū:], longi u, wim in roof, id ekvos [ō:] wim in door…Un zav nevos is ea doʒ vido usvoken [ī:] wim in to read, o [e] wim in I've read.

Di moz duto a komic misincepade. I lisì unvos su u sigèl in de kafeteria u kampiu in Salzburg, Osteria: "There is bear tonight" (Je ste bars di vespen). I sì naturim antolsan gusto bars po de pri vos in mi ʒiv, ba i sì mol disluʒen: instà bars, je stì solem bir (beer).

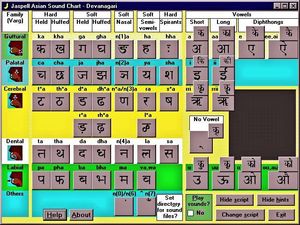

Sim, wan un lis de Engli traskrivad un alten lingu, un moz nevos so siuri ov de zone da lingu. I av usperijen da ki Hindi. Hindi vid skriven in de devanāgarī alfabèt id de majsan Europane doʒ uzo u traskrivad po mozo liso ja. Mol poje zoce vidì publizen ov Hindi in franci; mole publizade se in Engli.

Anlezide inìz ki bazi vorde wim de verb "so", po samp: Mi nom se Rāma = in Hindi Merā nām Rāma hæ: je se nerim Uropi vord pos vord, ba di s'ne de Engli traskrivad: "hæ" se de traskrivad IFA (Intranasioni Fonetiki Alfabeti). In eke Hindi-Engli leribibe, je vid skriven "hA", in altene "hai", simte i zavì ne is un doʒì usvoko [hā], [ha], [hai], [he] o [hæ]. De som obesinid usvèn ki de litèr u: ekvos je vid uzen po traskrivo de zon [∧], ekvos po de zon [u] = de kurti u, id de longi u vid ekvos traskriven oo, we in Engli moz os so kurti. Di usklàr parkà de Hindi vord jangal (fost) vidì jungle in Engli, ki maj o min u somi usvòk, obte dapòs je vidì ʒungel usvoken [ʒung…dʒung…] ki [u] in de majsan alten Europan lingas: po s. Itali giungla, Doski Dschungel, Rumàni junglă, Kroati džungla, Rusi джунгли, Albàni xhungël, Greci ζούγκλα.

Altenzatim je ste nun problèm ki Engli kozone po traskrivo Hindi sat lezim. Je se maj anlezi traskrivo Hindi ki Itali kozone. Un dia in Roma, i findì in u biboria du vordare: Sanskriti-Itali, id Hindi-Itali wen i kopì; sule vordare esìst ne in Franci, o se mol rari. Ki Itali, un moz traskrivo Hindi vokali zone ane probleme. De probleme inìz ki kozone.

In Itali c id g, for i id e, vid usvoken [t∫] "tc" id [dʒ], wa koruvòk a Hindi kozone: cînî "tcīnī" = Cini, gîvit "dʒīvit" = ʒivi. Pur, for a, o, u, lu vid usvoken "k" id "g": casa "kaza" = has, gatto "gat-to" = kat; sim un doʒ ajuto un i pos c id g po begaro de zone "tc" id "dʒ": ciascuno "tcaskuno" = jakun, giacca "dʒak-ka" = ʒak. Po Hindi vorde nu ve avo de traskrivad ciakr "tcakr" = kirk id giañgal "dʒañgal" = fost. Pur Hindi av os proflesen kozone wim dh, th, bh, ph, dʒh, tch…; po de majsan kozone, je sat ajuto h pos de kozòn in de Itali traskrivad: dh, th, bh… De problèm inìz ki de litere c id g: in Itali, h vid ajuten a c id g po odteno de zone "k" id "g" for i id e, po samp ci = "tci" id ge = "dʒe", ba che = "ke" id ghi = "gi". Kim ʒe traskrivo de Hindi proflesen kozone "tch" id "dʒh", po samp in "tchoṭā" = miki o "dʒhūṭh" = luʒ ? De Itali traskrivad doʒ uzo sige wim "⊄" id "ğ": "⊄hoṭâ" id "ğhūṭh".

Tal da se mol koplizen id i men te de Indian governad doʒev adopto u maj adapten intranasioni traskrivad po Hindi id alten Indian lingas, bazen su IFA o alten intranasioni alfabete - ba subetàl ne su Engli - wim Cine detì ki pīnyīn.

* * *

Devanagari alfabèt

* * *

Metad id Olìve

Pur de cevi problèm ki Engli wan un vol usploro o slim vido informen ov u novi linga se alten. Molilingu vordare wim Google Translator se mol pratiki, ba lu se bazen su Engli, wa dut a mole irade. Wan un cek de eglivalte de Franci vordi "pipe" (pipa) o Nizilandi "pijp" in Doski po samp, un ve findo Rohr (tub), o in Greci σωλήνας (tub), par in Engli "pipe" sin obe tub id pipa, id Google av becizen te u tub se maj vezi te u pipa. Wan un kon Doski id Greci, je s'ne tio pej, ba kim zavo is de Esti, Fini, Azeri, Indonesi, Telugu, Tagalogi vorde sin tub o pipa ? Is un cek de vord prosès, po samp in Franci "procès", un ve findo Versuch (= prob) in Doski instà de vord Prozess we se de Doski eglivàlt (VZ Franz Kafka Der Prozess). Parkà ? Par in Engli, prosès se trial; ba trial sin os "prob" < to try = probo, id "uspròb". Sim, cekan "prosès", un ve findo in Rusi po samp изпытание = uspròb, in Nizilandi onderzoek = procekad, stud, in Dani forsøg = prob, in Espàni juicio id in Slovaki súd we sin obe "ʒudad", in Latvi izmēģinājums = uspròb, id sim pro… Anmozli findo de regi eglivalte. Je se ʒe slim ansini !

Jok pejes, nome id verbe av de som form in Engli. Sim wan un cek "change" in alten lingas, un zav nevos is un ve odteno "meto" o "metad". Po samp, wan un cek de eglivalte po de Franci verb "changer", un ve findo It. cambiare, Lit. keisti, Da ændre, Lat mutare = meto, ba os Do. Änderung, Nz verandering, Es cambio, Ltv. maiņa, Gr. αλλαγή = metad. Id ka sin de slogan vorde: Hin. parivartan, Tag baguhin, Indo. perubahan, Swa. mabadiliko, Telu. mārpu = meto o metad ?

Paralelim, mole Engli vorde se obe nome id adjetive, wim de Franci-Engli vord"orange" we sin arànʒ id aranʒi. De Engli vord "olive" po samp se u nom (= olìv), ba je moj os so un adjetìv, wim in "olive tree" = olivi drev (olivar). Sim de eglivalte daven po de Franci vord "olive" pa Google Translator sin ekvos "olìv" wim Do. Olive, Sw oliv, Nz olijf, It., Kat., Por oliva, Gr. ελιά, Kr. maslina, Ar. zeitun, Azer zeytun, Indo. zaitun, ekvos "olivi" wim Alb ulliri, Tc. Slk. olivový, Pol oliwkowy, Slo oljčno, Ltv. olīvu, Lit. alyvuogių… Ba kim zavo ka sin Esti oliiviõli, Fin. oliiv, Beng. jalapā'i, Geor. zet'iskhilis…, olìv o olivi ?

Di s'u veri katastròf; ka moz un deto ? Provero jaki vord in u disemi dulingu vordar (wan lu esìst; Esti o Telugu vordare se priʒe rari), o deto mole irade ? Engli se verim ne adapten po vido uzen wim u pontilinga intra moldi lingas.

* * *

John Constable: De bij kwal

* * *

De l'anglais, du hindi et des autres langues

* * *

Problèmes de transcription

Je trouve que l'anglais n'est pas la solution idéale pour la transcription d'autres langues.

La prononciation

La première difficulté que l'on rencontre lorsque l'on veut transcrire à l'aide de l'anglais une langue qui n'utilise pas les caractères latins est due à la prononciation anglaise. L'anglais, comparé à la plupart des autres langues européennes a des voyelles aux sonorités très particulières. En outre chaque lettre correspondant à une voyelle ou chaque groupe de voyelles n'a pas une, mais plusieurs prononciations très différentes.

Par exemple a peut se prononcer [ə] comme dans l'article a = un, [ei] comme dans cake, [ā:] comme dans car, [ō:] comme dans all, [æ] comme dans cat…; e peut se prononcer [e] comme dans bed, [ī:] comme dans evening, parfois [i] comme dans women, chicken, etc., i peut se prononcer [i] comme dans pig, [ai] comme dans life…, o peut se prononcer [o] comme dans not, [əu] comme dans nose… u peut se prononcer [∧] comme dans cut, [jū:] "yoû" comme dans tube, parfois [ū:] "oû" comme dans sure.

Nous avons le même problème avec les groupes de voyelles et les diphtongues: oo se prononce [u], ou court, comme dans book, ou [ū:], ou long, comme dans roof, et parfois [ō:] comme dans door…On ne sait jamais si ea doit se prononcer [ī:] comme dans to read, ou [e] comme dans I've read.

Cela peut créer des malentendus assez drôles. J'ai lu une fois à la cafétéria d'un camping de Salzburg: "There is bear tonight" (Ce soir il y a de l'ours). J'étais bien sûr impatient de goûter à de l'ours pour la première fois de ma vie, mais j'ai été très déçu: en fait d'ours, il n'y avait que de la bière (beer).

Ainsi, quand on lit la transcription anglaise d'une autre langue, on ne peut jamais être assuré d'avoir une idée, même approximative, des sonorités de cette langue. J'en ai fait l'expérience avec le hindi. Le hindi s'écrit avec l'alphabet devanāgarī et la plupart des Européens doivent avoir une transcription pour pouvoir le lire. Très peu de choses ont été publiées sur le hindi en français; la plupart des publications sont en anglais.

Les difficultés commencent avec les mots de base comme le verbe "être", par exemple: Je m'appelle Rāma = en hindi Merā nām Rāma hæ: c'est presque de l'Uropi mot à mot (Mi nom se Rāma), mais ce n'est pas là la transcription anglaise: "hæ" correspond à l'Alphabet Phonétique International API. Dans certains manuels de hindi en anglais, il est retranscrit "hA", dans d'autres "hai", si bien que je ne savais plus si je devais prononcer [hā], [ha], [hai], [he] ou [hæ]. La même ambiguité se retrouve avec la lettre u: elle est parfois utilisée pour transcrire le son [∧], parfois pour le son [u] = ou court, et le ou long est retranscrit oo, qui peut également correspondre au ou court en anglais. Ceci explique pourquoi le mot hindi jangal (forêt) est devenu jungle en anglais, avec une prononciation à peu près conforme à l'original, mais qui est ensuite devenu jungle prononcé "joung… djoung…" avec "ou" [u] (à cause du "u" anglais) dans la plupart des autres langues européennes: par ex. italien giungla, allemand Dschungel, roumain junglă, croate džungla, russe джунгли, albanais xhungël, grec ζούγκλα…

En revanche, il n'y a aucun problème avec les consonnes anglaises pour transcrire le hindi relativement facilement. C'est beaucoup plus difficile de le transcrire avec des consonnes italiennes. Un jour à Rome, j'ai trouvé dans une librairie deux dictionnaires: sanskrit-italien, et hindi-italien, que j'ai bien sûr achetés; de tels dictionnaires n'existent pas en français, ou sont très rares. Avec l'italien, on peut transcrire les voyelles hindi sans problème. Les problèmes commencent avec les consonnes.

En italien c et g, devant i et e, se prononcent [t∫] "tch" et [dʒ] "dj", qui correspondent à des consonnes hindi: cînî "tchīnī" = Chinois, gîvit "djīvit" = vivant. Cependant, devant a, o, u, ces lettres se prononcent "k" et "gu": casa "caza" = maison, gatto "gat-to" = chat; on doit donc ajouter un i après le c et le g pour conserver les sons "tch" et "dj": ciascuno "tchascuno" = chacun, giacca "djac-ca" = veste. Pour des mots hindi nous aurons la transcription suivante: ciakr "tchakr" = cercle et giañgal "djañgal" = forêt. Mais le hindi a aussi des consonnes aspirées comme dh, th, bh, ph, djh, tch…; pour la plupart de ces consonnes, il suffit d'ajouter un h après la consonne dans la transcription italienne: dh, th, bh… Le problème commence avec les lettres c et g: en italien, si l'on ajoute h après c et g on obtient les sons "k" et "gu" devant i et e, par exemple ci = "tchi" et ge = "djé", mais che = "ké" et ghi = "gui". Comment donc transcrire les consonnes aspirées hindi "tchh" et "djh", par exemple dans "tchhoṭā" = petit ou "djhoûṭh" = mensonge ? La transcription italienne doit utiliser des signes comme "⊄" et "ğ": "⊄hoṭâ" et "ğhūṭh".

Tout cela est bien compliqué et je crois que le gouvernement indien aurait intérêt à adopter un système de transcription international mieux adapté pour le hindi et les autres langues indiennes, basé sur l'API ou d'autres alphabets internationaux - mais surtout pas sur l'anglais - comme l'ont fait les Chinois avec le pīnyīn.

* * *

Sanskriti

* * *

Le changement et les olives

Cependant, le problème essentiel de l'anglais lorsque l'on veut explorer ou tout simplement s'informer sur une nouvelle langue est tout autre. Des dictionnaires multilingues comme Google Translator sont très pratiques, mais ils sont basés sur l'anglais, ce qui provoque un grand nombre d'erreurs. Lorsque l'on cherche les équivalents du mot français "pipe" ou néerlandais "pijp" en allemand par exemple, on trouvera Rohr (tuyau), ou en grec σωλήνας (tuyau), car en anglais "pipe" signifie à la fois tuyau et pipe, et Google a décidé qu'un tuyau était plus important qu'une pipe. Quand on connaît l'allemand et le grec, ce n'est pas trop grave, mais comment savoir si le mot estonien, finnois, azéri, indonésien, telougou, tagalog signifient tuyau ou pipe ? Si l'on cherche le mot procès, par exemple, on trouvera Versuch (= essai) en allemand au lieu du mot Prozess qui en est l'équivalent (cf Franz Kafka Der Prozess). Pourquoi ? Parce qu'en anglais, procès se dit trial; qui signifie aussi "essai" < to try = essayer, et "épreuve". Ainsi, en cherchant "procès", on trouvera en russe par exemple изпытание = épreuve, en néerlandais onderzoek = recherche, étude, en danois forsøg = essai, en espagnol juicio et en slovaque súd qui signifient tous les deux "jugement", en letton izmēģinājums = épreuve, etc… Impossible de trouver l'équivalent exact. C'est tout simplement insensé !

Pire encore, les noms et les verbes ont la même forme en anglais. Si bien que lorque l'on cherche "change" dans d'autres langues, on ne sait jamais si l'on obtiendra l'équivalent de "changer" ou de "changement". Par exemple, en cherchant le verbe français "changer", on trouve it. cambiare, lit. keisti, da ændre, lat mutare = changer, mais aussi al. Änderung, nd verandering, es cambio, let. maiņa, gr. αλλαγή = changement. Que signifient donc les mots suivants: hin. parivartan, tag baguhin, indo. perubahan, swa. mabadiliko, telou. mārpu = changer ou changement ?

Parallèlement, de nombreux mots anglais sont à la fois des noms et des adjectifs, comme le mot franco-anglais "orange" qui désigne le fruit et la couleur. Le mot anglais "olive" par exemple est un nom (= olive), mais il peut aussi être un adjectif "= d'olive", comme dans "olive oil" = huile d'olive. Ainsi les équivalents donnés pour le mot français "olive" par Google Translator signifient tantôt "olive" comme al. Olive, sué oliv, nd olijf, it., cat., por oliva, gr. ελιά, cr. maslina, ar. zeitun, azer. zeytun, indo. zaitun, tantôt "d'olive, à olives" comme alb ulliri, tch. slk. olivový, pol oliwkowy, slo oljčno, let. olīvu, lit. alyvuogių… mais comment savoir ce que signifient l'estonien oliiviõli, fin. oliiv, beng. jalapā'i, géor. zet'iskhilis…, olive ou d'olive ?

C'est un vrai désastre; comment y remédier ? Chercher chaque mot dans un dictionnaire bilingue différent (quand ils sont disponibles; les dictionnaires d'estonien ou de télougou ne courent pas les rues), ou accepter de faire un grand nombre d'erreurs ? L'anglais n'est vraiment pas adapté pour servir de langue-pont entre les langues du monde.

* * *

The Lady of Shalott, Pre-rafaeliti picten

* * *

On English, Hindi and other languages

* * *

Problems of transcription

I find English is far from being the ideal solution for the transcription of other languages.

Pronunciation

The first difficulty you meet when you want to transcribe a language not using Latin scripts with the help of English is due to English pronunciation. Compared to the majority of other European languages, English has vowels with peculiar sounds indeed. Besides, each letter corresponding to a vowel, or each group of vowels or diphthongs doesn't have one, but several very different pronunciations.

For example a can be pronounced [ə] as in the article a, [ei] as in cake, [ā:] as in car, [ō:] as in all, [æ] as in cat…; e can be pronounced [e] as in bed, [ī:] as in evening, sometimes [i] as in women, chicken, etc., i can be pronounced [i] as in pig, [ai] as in life…, o can be pronounced [o] as in not, [əu] as in nose… u can be pronounced [∧] as in cut, [jū:] as in tube, sometimes [ū:] as in sure.

We have the same problem with groups of vowels and diphthongs: oo is pronounced [u], short oo, as in book, or [ū:], long oo, as in roof, and sometimes [ō:] as in door… You never know when ea should be pronounced [ī:] as in to read, ou [e] as in I've read.

This may give rise to rather funny misunderstandings. I remember once reading a notice in the cafeteria of a Salzburg camping site: "There is bear tonight". I just couldn't wait to taste bear for the first time in my life, But I was terribly disappointed: instead of bear, there was only beer.

Thus when you read the English transcription of another language, you can never be sure to get the right pronunciation, the right sounds, even approximately. I experienced this with Hindi. Hindi is written with the devanāgarī alphabet and most Europeans need a transcription to be able to read it. There are very few publications on Hindi in french; most of them are in English.

The difficulties begin with basic words like the verb "to be", for example: My name is Rāma = in Hindi Merā nām Rāma hæ: it is almost Uropi, or English word for word, but the English transcription is different: "hæ" corresponds to the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA). In certain Hindi-English handbooks, it is transcribed as "hA", in other "hai", and in the end you no longer know whether you should pronounce [hā], [ha], [hai], [he] or [hæ]. There is a similar ambiguity with the letter u: it is sometimes used to transcribe the sound [∧], sometimes for the sound [u] = short oo, the long oo being transcribed oo, though it may also correspond to the short oo in English. This explains why the Hindi word jangal (forest) has become jungle in English, with a pronunciation relatively close to the original, but which has later been pronounced "joong… zhoong…" in most other European languages with [u] "oo" (because of the English "u" transcribing the Hindi "a"): for ex. Italian giungla, German Dschungel, Rumanian junglă, Croatian džungla, Russian джунгли, Albanian xhungël, greek ζούγκλα…

On the other hand, there is no problem with English consonants to transcribe Hindi relatively easily. It is much more difficult to transcribe it with Italian consonants. One day in Rome, in a bookshop I found two dictionaries: Sanskrit-italian, and Hindi-italian; I bought them of course: such dictionaries do not exist in French, or are extremely rare. With Italian, you can transcribe Hindi vowels without any problem. The problems start with the consonants.

In Italien c and g, before i and e, are pronounced [t∫] "ch" and [dʒ] "j", which correspond to Hindi consonants: cînî "chīnī" = Chinese, gîvit "jīvit" = living. However, before a, o, u, these letters are pronounced "k" et "g" as in give: casa "kaza" = house, gatto "gat-to" = cat; you have to add an i after the c and the g to preserve the sounds "ch" and "j": ciascuno "chascuno" = each one, giacca "jac-ka" = jacket. For Hindi words we'll have the following transcription: ciakr "chakr" = circle and giañgal "jañgal" = forest. But Hindi also has aspirated consonants like dh, th, bh, ph, jh, tch…; for most of these consonants, you only need to add an h after the consonant in the Italian transcription: dh, th, bh… The problems start with the letters c and g: in Italian, when you add an h after c and g you get the sounds "k" and [g] (as in give) with i and e, for example ci = "chi" and ge = "jay", but che = "kay" and ghi = "gi". How on earth can we transcribe the Hindi aspirated consonants "chh" and "jh", for instance in "chhoṭā" = small or "jhooṭh" = a lie ? The Italian transcription has to resort to signs like "⊄" and "ğ": "⊄hoṭâ" and "ğhūṭh".

All this is very complicated and I think the Indian government had better adopt an international transcription system better suited to Hindi and the other Indian langues, based on IPA or other international alphabets - but certainly not on English -, as the Chinese did with pīnyīn.

* * *

Devanagari alfabèt

* * *

Change and olives

However, the essential problem with English, when you want to explore or simply get some information on a new language, is quite another matter. Multilingual dictionaries like Google Translator are very convenient, but they are based on English, which may cause a great deal of errors. When you look for the equivalents of the French word "pipe" or Dutch "pijp" in German for instance, you will find Rohr (water pipe), or in Greek σωλήνας (water pipe), because in English "pipe" means both a pipe for water, and a pipe for smoking; apparently Google decided that water supplying was more important than smoking. When you know German and Greek, it doesn't really matter, but how can you know whether the Estonian, Finnish, Azerbaijani, Indonesian, Telugu, Tagalog words mean a pipe for water or for smoking ? When you look for the word procès, for example in French (= trial in court), you will find findo Versuch (= a test) in German instead of the word Prozess which is the equivalent (cf Franz Kafka Der Prozess). Why ? Because in English, trial can refer to legal proceedings in court, but trial also means "a test" < to try = to attempt, and eventually "hardship" (the trials of old age, for example). Thus, when to look for Fr. procès, or Ger. Prozess, you will find изпытание in Russian for example = hardship, in Dutch onderzoek = research, study, in Danish forsøg = test, in Spanish juicio and in Slovakian súd which both mean "judgement", in Latvian izmēģinājums = hardship, and so on… Impossible to find the right equivalent. It's sheer nonsense !

Worse still, nouns and verbs have the same form in English. So that when you look for "change" in other languages, you never know whether you'll find the equivalent of "to change" or of "a change". For example, when you type the French verb "changer", you get It. cambiare, Lit. keisti, Da ændre, Lat mutare = to change, but also Ger. Änderung, Dutch verandering, Sp. cambio, Latv. maiņa, Gr. αλλαγή = a change. What on earth do the following words mean ?: Hin. parivartan, Tag baguhin, Indo. perubahan, Swa. mabadiliko, Telu. mārpu = to change or a change ?

In the same way, many English nouns can be used as adjectives, like the French-English word "orange" which can mean the fruit or the colour. The English word "olive" for instance is a noun which can also be used as an adjective: "olive-", as in olive oil or olive tree. Thus, the equivalents given for the French word "olive" by Google Translator sometimes mean "an olive" as in Ger. Olive, Swe. oliv, Dutch olijf, It., Cat., Por oliva, gr. ελιά, Cr. maslina, Ar. zeitun, Azer. zeytun, Indo. zaitun, sometimes "olive-", relating to olives, as in Alb ulliri, Cz., Slk. olivový, Pol oliwkowy, Slo oljčno, Latv. olīvu, Lit. alyvuogių… but how can you know whether Esthonian oliiviõli, Fin. oliiv, Beng. jalapā'i, Geor. zet'iskhilis…, are nouns or adjectives ?

This is a real disaster; but what can we do about it ? Look up each word in a different bilingual dictionary (when they exist; Esthonian or Telugu dictionaries are rather hard to find), or accept to make a lot of mistakes? English is really not suited to serve as a "bridge language" between the languages of the world.

* * *

John Constable: Stratfordi mulia

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F2%2F7%2F277026.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F31%2F61%2F321345%2F134515231_o.jpeg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F19%2F44%2F321345%2F134293494_o.jpeg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F01%2F79%2F0%2F134280602_o.jpeg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F42%2F21%2F321345%2F133835185_o.jpeg)