Uropi vorde: etimologij - étymologie - etymology B

* Uropi Nove 85 * Uropi Nove 85 * Uropi Nove 85*

Mias - viande - meat - miaso - Fleich

De Indeuropan rod *mēmsom davì de vord mias in tale Slavi lingas (miaso, meso…), in Lituvi (mėsa + Latvi miesa = karn) id Albàni (mish), da se in 13 lingas, a wen nu moz ajuto Armèni mis id Indian lingas: Sanskriti māmsám, Hindi māñs, Bengali, Gudʒarati, Marathi, Kannada mānsa, Nepali māsu, Penʒabi māsa, id Romani mas, da se 22 lingas. Pardà nu av Uropi mias.

Pos nu av de Latini caro, carnis we davì carne = mias in 6 Romaniki lingas, pos de Skandinavi kød, kött… in 4 lingas, de Germàni Fleich, vlees (+ Engli flesh = karn), de Kelti kig, cig, de Balti-Fini liha in 3 lingas. Tale de alten vorde esìst solem in un linga.

La racine indo-européenne*mēmsom a donné le mot viande dans toutes les langues slaves (miaso, meso…), en lituanien (mėsa + letton miesa = chair) et en albanais (mish), soit dans 13 langues, auxquelles on peut ajouter l'arménien mis et les langues indiennes: sanskrit māmsám, hindi māñs, bengali, gudjarati, marathi, kannada mānsa, népali māsu, penjabi māsa, et le romani mas, soit 22 langues. D'où l'Uropi mias.

Vient ensuite le mot latin caro, carnis qui a donné carne = viande dans 6 langues romanes, puis le terme scandinave kød, kött… dans 4 langues, le germanique Fleich, vlees (+ l'anglais flesh = chair), le celte kig, cig, le balto-finnois liha dans 3 lingas. Tous les autres termes n'existent que dans une seule langue.

The Indo-European root *mēmsom gave the word meat in all Slavic languages (miaso, meso…), in Lithuanian (mėsa + Latvian miesa = flesh) and Albanian (mish), that is in 13 languages, to which we can add Armenian mis and Indian languages: Sanskrit māmsám, Hindi māñs, Bengali, Gujarati, Marathi, Kannada mānsa, Nepali māsu, Punjabi māsa, and Romani mas, that is 22 languages. Thus we have Uropi mias.

Then there is Latin caro, carnis which gave carne = meat in 6 Romance languages, then Scandinavian kød, kött … in 4 languages, Germanic Fleich, vlees (+ English flesh), Celtic kig, cig, Baltic Finnic liha in 3 languages. All the other words exist in one language only.

Miel - miel - honey - miod - meli

De vord miel in Europan lingas ven prim od du mol neri Indeuropan rode. De pri se *mélid we davì de Romaniki vorde: miel, miele, mel…, Greci meli, Albàni mjaltë, Armèni mełr, id de Kelti vorde: mil, mel…, da se 15 lingas. De duj se *medhu we davì tale de Slavi id Balti vorde: mjod, med, medus…, da se 13 lingas. De du Fini-Ugri vorde: méz, mesi moj avo de som odvenad. Sim nu av Uropi miel.

Pos je ste de Germàni vorde: honey, Honig, honung…, in 7 lingas, id de Turki vorde: bal in 4 lingas.

Le mot miel dans les langues européennes vient en premier lieu de deux racines indo-européennes très proches. La première est *mélid qui a donné les termes romans: miel, miele, mel…, le grec meli, l'albanais mjaltë, l'arménien mełr, et les mots celtes: mil, mel…, soit 15 langues. La seconde est *medhu qui a donné tous les termes slaves et baltes: mjod, med, medus…, soit 13 langues. Les deux mots finno-ougriens: méz, mesi ont peut-être la même origine. Nous avons donc miel en Uropi.

Viennent ensuite les termes germaniques: honey, Honig, honung…, dans 7 langues, et les mots turcs: bal dans 4 langues.

The word honey in European languages stems from two very close Indo-European roots. The first is *mélid which gave the Romance words: miel, miele, mel…, Greek meli, Albanian mjaltë, Armenian mełr, and the Celtic words mil, mel…, that is 15 languages. The second is *medhu which gave all the Slavic and Baltic terms: mjod, med, medus…, that is 13 words. The two Finno-Ugric words méz, mesi may have the same origin. Thus we have miel in Uropi.

Then there are the Germanic terms: honey, Honig, honung…, in 7 languages, and the Turkish words: bal in 4 languages.

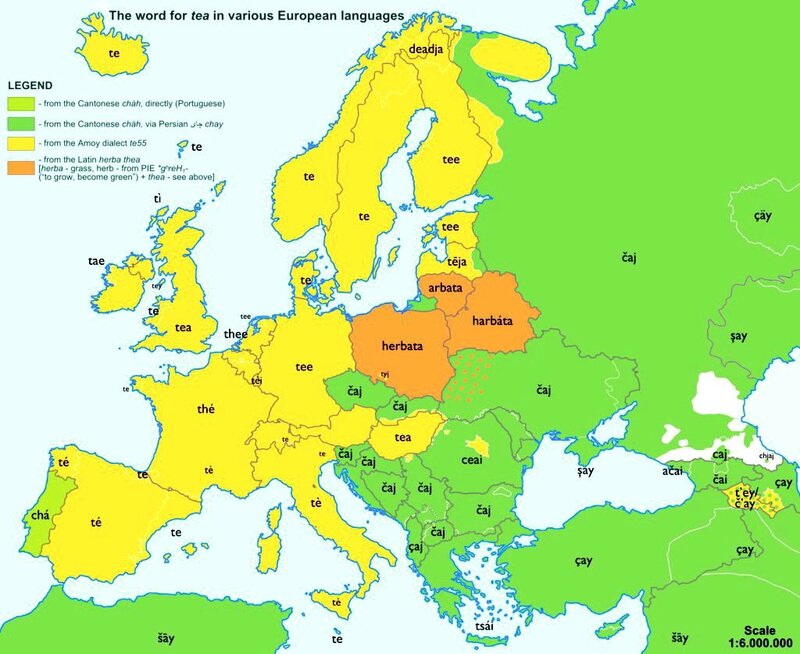

Tej - thé - tea - te - čaj

De vorde po tej in Europan lingas ven cevim od du Cini vorde: te od de Amoj dialèkt voken in de Fujian provìns in sudosti Cinia, id cháh od de Kantongi linga (Guǎngdōng Huà) voken in de Guangdong provìns bezàt. 23 lingas in Europa uz de vord te, tea, Tee a wen un moz ajuto Indonesi o Malàj teh, Khmer te, Maori tī, Tamili tēyilai, Telugu tēyāku, id 13 de vord čaj, mole maj is un ajùt de Midosti lingas: Turki, Arabi, Georgi, Persi, Kurdi id 7 Indian lingas. De Uropi vord tej, we koruvòk a Latvi teja, se u sort kompromizi intra te id čaj.

Usim da, 3 lingas: Polski, Lituvi, Bielorusi uz vorde we ven od u Latin usprès: herba thea = herbitej.

Les mots pour thé dans les langues européennes viennent essentiellement de deux mots chinois: te du dialecte Amoy parlé dans la province de Fujian dans le sud-est de la Chine, id cháh du Cantonais (Guǎngdōng Huà) parlé dans la province voisine de Guangdong. 23 langues en Europe utilisent le mot te, tea, Tee, auxquelles on peut ajouter l'indonésien ou malais teh, le khmer te, le maori tī, le tamoul tēyilai, le télougou tēyāku, et 13 le mot čaj, beaucoup plus si on ajoute les langues du Moyen-Orient: turc, arabe, géorgien, persan, kurde et 7 langues indiennes. Le mot Uropi tej, qui correspond au a letton teja, est une sorte de compromis intre te et čaj.

En dehors de cela, 3 langues: le polonais, le lituanien, le biélorusse utilisent des termes qui sont issus d'une expression latine: herba thea = thé d'herbes.

The words for tea in European languages stem essentially from two Chinese words: te from the Amoy dialect spoken in the Fujian province in south-eastern China, and cháh from Cantonese (Guǎngdōng Huà) spoken in the neighbouring Guangdong province. 23 languages in Europe use the word te, tea, Tee to which we can add Indonesian or Malay teh, Khmer te, Maori tī, Tamil tēyilai, Telugu tēyāku…, and 13 the word čaj, many more if we add Middle-East languages: Turkish, Arabic, Georgian, Persian, Kurdish and 7 Indian languages. The Uropi word tej, which corresponds to Latvian teja, is a kind of compromise between te and čaj.

Apart from this, 3 languages: Polish, Lithuanian, Belarusian use words that stem from a Latin expression: herba thea = herb tea.

Roz - rose - ruža - roos - triandafyllo

Tale Europan vorde po roz sem veno od de som Indeuropan rod: *wṛdhos = vilgiroz, we davì: rosa, ros, růže, ruusu…, ba os Arabi warda, Armèni vard, Georgi vardi, tra Indo-Irani *Hwardh-. Da se in tal eke 33 lingas we davì Uropi roz.

De usnemade inklùz Greci triantafyllo (trides petale) we davì Albàni trendafil, Rumàni trandafir, Ukraini troyanda, id altenzatim, Slovèni vrtnica (od gardin).

Tous les termes européens pour rose semblent venir de la même racine indo-européenne: *wṛdhos = églantine, qui a donné: rosa, ros, růže, ruusu…, mais aussi l'arabe warda, l'arménien vard, le géorgien vardi, par l'intermé-diaire de l'indo-iranien *Hwardh-. Soit en tout quelques 33 lingas qui ont donné l'Uropi roz.

Les exceptions incluent le grec triantafyllo (trente pétales) qui a donné l'albanais trendafil, le roumain trandafir, l'ukrainien troyanda, et par ailleurs le slovène vrtnica (fleur) du jardin).

All European words for rose seem to stem from the Indo-European root *wṛdhos = sweetbriar, which gave: rosa, ros, růže, ruusu…, but also Arabic warda, Armenian vard, Georgian vardi, through Indo-Iranian *Hwardh-. That is in all some 33 languages which gave Uropi roz.

Exceptions inklude Greek triantafyllo (thirty petals), which gave Albanian trendafil, Rumanian trandafir, Ukrainian troyanda, and on the other hand, Slovene vrtnica (from the garden).

Soin - rêve - dream - sogno - son

De majsan Europan vorde po soin ven od de Indeuropan rod *swopnyom = soin, kovigen a de rod sinan sopo, sop, da se *swepmi, *swopnos. Je davì de vorde po soin cevim in Romaniki (sogno, sueño, sonho…), Slavi (son, sen, san…) id Balti (sapnis, sapnas) lingas, da se in 15 lingas, a wen nu moz ajuto Rusi son (sop, soin), Franci songe, id os Hindi, Nepali sapnā, Bengali sbapna, Gudʒarati, Marathi svapna, Penʒabi supanē, da se 23 lingas. Od wo Uropi soin.

Pos nu av de Germàni vorde: dream, Traum, dröm…, da se 8 lingas, de Rusi id Bulgàri mečta, id vorde esistan solem in un linga, wim Franci rêve, Greci oneiro, Rumàni vis, Bielorusi mara, Hungàri álom, Armèni yeraz…

Le mot pour rêve dans la plupart des langues européennes, est issu de la racine indo-européenne *swopnyom = rêve, apparentée à la racine qui signifie dormir, sommeil: *swepmi, *swopnos. Elle a donné le mot rêve essentiellement dans les langues romanes (sogno, sueño, sonho…), slaves (son, sen, san…) et baltes (sapnis, sapnas), soit dans 15 langues, auxquelles on peut ajouter le russe son (sommeil, rêve), le français songe, ainsi que le hindi et népali sapnā, le bengali sbapna, le gudjarati et marathi svapna, le penjabi supanē, soit 23 langues. D'où le mot Uropi soin.

Viennent ensuite les mots germaniques: dream, Traum, dröm…, soit 8 langues, le russe et le bulgare mečta, et les mots qui n'existent que dans une seule langue, comme le français rêve, le grec oneiro, le roumain vis, le biélorusse mara, le hongrois álom, l'arménien yeraz…

Most of the European words for dream stem from the Indo-European root *swopnyom = dream, related to the root meaning sleep, to sleep, i-e *swopnos, *swepmi,. It gave the words for dream mainly in Romance (sogno, sueño, sonho…), Slavic (son, sen, san…) and Baltic (sapnis, sapnas) languages, that is in 15 languages, to which we can add Russian son (sleep, dream), French songe, as well as Hindi, Nepali sapnā, Bengali sbapna, Gujarati, Marathi svapna, Punjabi supanē, that is 23 languages. Hence Uropi soin.

Then we have the Germanic words: dream, Traum, dröm…, that is 8 languages, Russian and Bulgarian mečta, and words existing in one language only, like French rêve, Greek oneiro, Rumanian vis, Belarusian mara, Hungarian álom, Armenian yeraz…

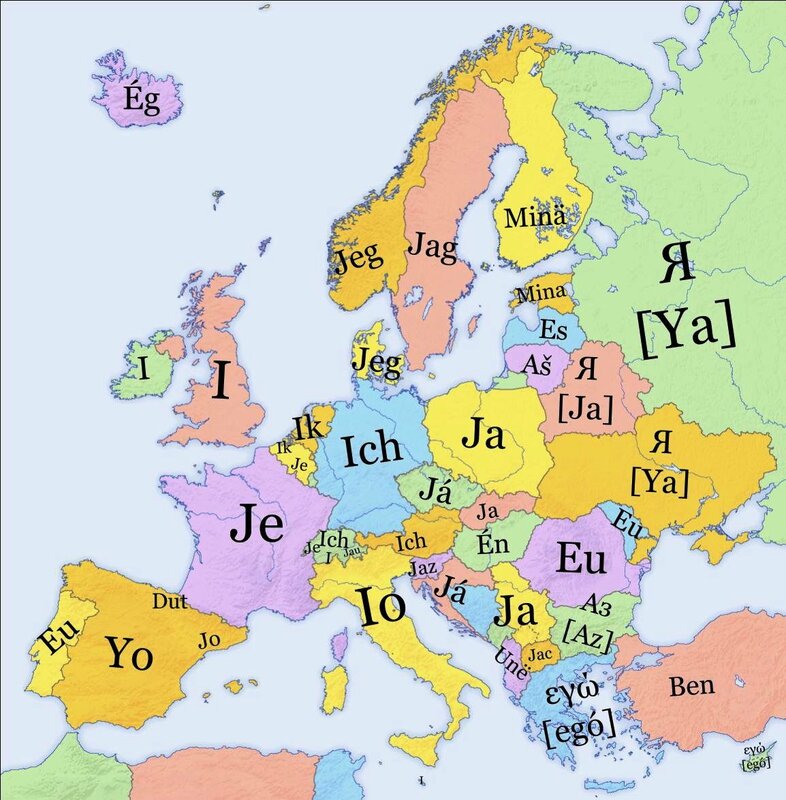

De pronòm i - je - I - io - ich - ja

Nerim tale de Europan vorde po de personi pronòm, pri persòn singular, subjèt = i ven od de Indeuropan pronòm: *egō, ba solem Greci id Skandinavi lingas av progaren semli forme: egô, eg, jeg, jag… Tale de alten forme inìz ki i : I, i, ik, ich, io o j (y): ja, jaz, jeg, jag, yo… Solem de Balti-Fini lingas (mina, minä) id Iri (mé) av u pronom we se semli a de Indeuropan pronòm in akuzatìv: *me, (de pronòm i daven po Iri su de map se un irad: i se de Kimri pronòm). Sim nu av de Uropi pronòm i.

La quasi-totalité des pronoms européens pour la première personne du singulier sujet (= je) proviennent du pronom indo-européen: *egō, mais seuls le grec et les langues scandinaves ont maintenu des formes semblables: egô, eg, jeg, jag… Toutes les autres formes de ce pronom commencent par un i : I, i, ik, ich, io ou un j (y): ja, jaz, jeg, jag, yo… Seules les langues balto-finnoises (mina, minä) et le gaélique irlandais (mé) ont un pronom sujet semblable à l'accusatif du pronom indo-européen: *me, (le pronom i donné sur la carte pour l'irlandais est une erreur: i est le pronom gallois). Nous avons donc le pronom Uropi i.

Nearly all the European pronouns for the first person subject in the singular (= I) stem from the Indo-European pronoun: *egō, but only Greek and Scandinavian languages have preserved similar forms: egô, eg, jeg, jag… All the other pronouns begin with an i : I, i, ik, ich, io or a j (y): ja, jaz, jeg, jag, yo… Only the Baltic Finnic languages (mina, minä) and Irish Gaelic (mé) have a pronoun which is similar to the Indo-European pronoun in the accusative: *me, (the pronoun i given for Irish on the map is an error: i is the Welsh pronoun). Thus we have the Uropi pronoun i.

Sol - soleil - sun - Sonne - solntse - îlios

In nerim tale Europan lingas, de vorde po sol ven od de Indeuropan rod: *sāwel (*sóh2wḷ) /genitìv: *swen-; po samp in Romaniki lingas: sol, sole, soleil…, in Germàni lingas: sun, zon, Sonne, sol…, in Slavi lingas: solntse, słońce, sunce…, in Balti lingas: saule, in Kelti lingas: heol, haul, in Greci: hêlios…, da se in 28 lingas a wen nu moz ajuto Indian lingas: Bengali, Gudʒarati, Kanada, Marathi, Nepali sūrya, Hindi sūraj, sūrya…da se 34 lingas. Sim nu av Uropi sol.

De usnemade inklùz de Fino-Ugri lingas: nap, päike, aurinko…, Albàni diell, Gaeli grian id Baski ekhi.

Dans la quasi-totalité des langues européennes, les mots qui désignent le soleil sont issus de la racine indo-européenne: *sāwel (*sóh2wḷ) /génitif: *swen-; par exemple dans les langues romanes: sol, sole, soleil…, dans les langues germaniques: sun, zon, Sonne, sol…, dans les langues slaves: solntse, słońce, sunce…, dans les langues baltes: saule, dans les langues celtiques: heol, haul, en grec: hêlios…, soit dans 28 langues, auxquelles on peut ajouter les langues indiennes: Bengali, Gudjarati, Kannada, Marathi, Népalais: sūrya, Hindi sūraj, sūrya… soit 34 langues. Ce qui donne le mot Uropi sol.

Font exception les langues finno-ougriennes: nap, päike, aurinko…, l'albanais diell, le gaélique grian et le basque ekhi.

In nearly all European languages, the words for sun stem from the Indo-European root *sāwel (*sóh2wḷ) /genitive: *swen-, for example in Romance languages: sol, sole, soleil…, in Germanic languages: sun, zon, Sonne, sol…, in Slavic languages: solntse, słońce, sunce…, in Baltic languages: saule, in Celtic languages: heol, haul, in Greek: hêlios…, that is in 28 languages, to which you can add Indian languages: Bengali, Gujarati, Kannada, Marathi, Nepali sūrya, Hindi sūraj, sūrya…that is 34 lingas.

Exceptions include the Finno-Ugric languages: nap, päike, aurinko…, Albanian diell, Gaelic grian and Basque ekhi.

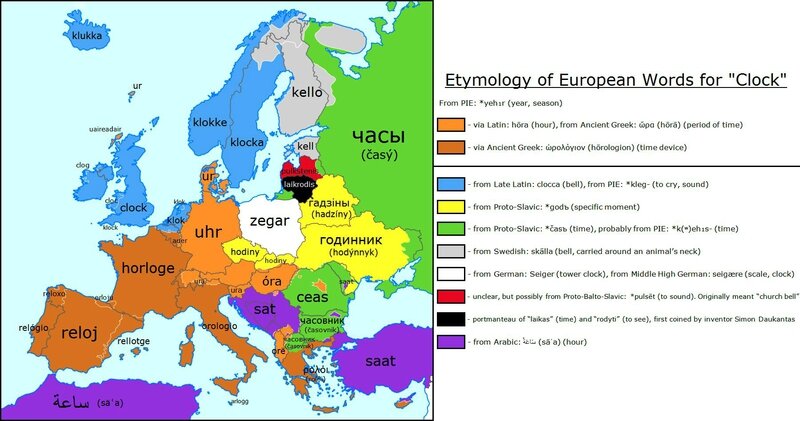

Horèl - horloge - clock - Uhr - časý - roloi

Mole Europan vorde po horèl vid formen ki de vord hor id (o ane) u sufìks. Di se de kaz in Slavi lingas: Rusi časý, Bulgàri časovnik (od čas = hor), Tceki hodiny, Ukraini hodynnyk (od hodina, hodyna = hor), id os in Romaniki lingas wej vorde po horèl ven od Greci hôrológion (aparèl) we dez de hor): Itali orologio, Portugi relógio, Franci horloge, Espani reloj… id moderni Greci roloi. Di se os de kaz in Uropi wo horèl ven od hor ki de sufìks -èl (= instrumènt). Alten lingas uz de som vord po hor id horèl: po samp Doski Uhr, Hungàri óra, Slovèni ura, Albàni orë, Serbi id Kroati sat, Turki saat, Arabi sā'a…

Altenzatim, mole Germàni lingas uz vorde we ven od nizi Latini clocca (= klol) od Kelti odvenad: clock, klok, klokke, klocka…; de Balti-Fini vorde ven od u Swedi vord sinan os klol: kell, kello. De alten vorde esìst solem in un linga: Polski: zegar, Latvi pulkstenis, Lituvi laikrodis…

De nombreux termes européens désignant l'horloge sont formés à partir du mot heure avec ou sans suffìxe. C'est le cas dans les langues slaves: le russe časý et le bulgare časovnik (de čas = heure), le tchèque hodiny, et l'ukrainien hodynnyk (de hodina, hodyna = heure), ainsi que dans les langues romanes dont les termes pour horloge viennent du grec hôrológion (appareil) qui dit l'heure): italien orologio, portugais relógio, français horloge, espagnol reloj… et grec moderne roloi. C'est également le cas en Uropi où horèl vient de hor = heure et du suffìxe -èl (= instrument). D'autres langues emploient le même mot pour heure et horloge: par exemple l'allemand Uhr, le hongrois óra, le slovène ura, l'albanais orë, le serbe et le croate sat, le turc saat, l'arabe sā'a…

Par ailleurs, de nombreuses langues germaniques utilisent des mots qui viennent du bas latin clocca (= cloche) d'origine celtique: clock, klok, klokke, klocka…; les langues balto-finnoises emploient des termes issus d'un mot suédois qui signifie également cloche: kell, kello. Les autres termes n'existent que dans une seule langue: polonais: zegar, letton pulkstenis, lituanien laikrodis…

Many European terms for clock are formed with the word hour with or without a suffìx. This is the case in Slavic languages: Russian časý, Bulgarian časovnik (from čas = hour), Czech hodiny, Ukrainian hodynnyk (from hodina, hodyna =hor), and also in Romance languages whose words for clock stem from Greek hôrológion (device) that tells the time): Italian orologio, Portuguese relógio, French horloge, Spanish reloj… and modern Greek roloi. It is also the case in Uropi where horèl = clock is formed with hor = hour and the suffìx -èl (= device). Other languages use the same word for hour and clock: for instance German Uhr, Hungarian óra, Slovene ura, Albanian orë, Serbian and Croatian sat, Turkish saat, Arabic sā'a…

On the other hand, many Germanic languages use words stemming from Late Latin clocca (= bell) from Celtic origin: clock, klok, klokke, klocka…; the Baltic Finnic terms stem from a Swedish word meaning bell as well: kell, kello. The other words exist in one language only: Polish: zegar, Latvian pulkstenis, Lithuanian laikrodis…

Kerk - église - church - kirke - cérkva - chiesa

De majsan Europan vorde po kerk ven od du disemi Greci vorde: kyriakon (has) de Siri (kyrios) id ekklêsia (asamij (de fedenis). De pri davì nerim tale Germàni id Slavi vorde: church, kerk, Kirche, kirk… id cerkov', cerkva, cărkvá… id os de Balti-Fini vorde: kirik, kirkko, da se vorde in 23 lingas, we davì de Uropi kerk. De duj, usim de moderni Greci eklisia, davì tale Romaniki vorde: église, iglesia, chiesa…, de Kelti vorde: iliz, eglwys, eaglais, id os Albàni kishë, Turki kilise, Georgi eklesia, Armèni yekeghets'i, Azeri kilsə, da se vorde in 15 lingas.

Usim da, nu av 3 Slavi vorde venan od de nizi Latini castellum (kastèl): Polski kościół, Tceki kostel id Slovaki kostol, du Balti vorde venan od veti Rusi boʒnitsa (has Doji): Latvi baznīca id Lituvi bažnyčia, Rumàni biserică we ven od Greci basilikê (vz basilika), id Hungàri templom (od Latini templum = tempel).

La plupart des termes européens pour église proviennent de deux mots grecs différents: kyriakon (maison) du Seigneur (kyrios) et ekklêsia (assemblée (des fidèles). Le premier a donné presque tous les mots germaniques et slaves: church, kerk, Kirche, kirk… et cerkov', cerkva, cărkvá… ainsi que les termes balto-finnois: kirik, kirkko, soit les mots de 23 langues, d'où l'Uropi kerk. Le second, en dehors du grec moderne eklisia, a donné tous les mots romans: église, iglesia, chiesa…, celtiques: iliz, eglwys, eaglais, ainsi que l'albanais kishë, le turc kilise, le géorgien eklesia, l'arménien yekeghets'i, l'azéri kilsə, soit les mots de 15 langues.

Par ailleurs, nous avons 3 mots slaves issus du bas latin castellum (château): le polonais kościół, le tchèque kostel et le slovaque kostol, deux mots baltes issus du vieux russe bojnitsa (maison de Dieu): le letton baznīca et le lituanien bažnyčia, puis le roumain biserică issu du grec basilikê (cf basilique), et le hongrois templom (du latin templum = temple).

Most European words for church stem from two different Greek words: kyriakon (house) of the Lord (kyrios) and ekklêsia (assemby (of the faithful). The first one gave nearly all Germanic and Slavic terms: church, kerk, Kirche, kirk… cerkov', cerkva, cărkvá… as well as the Baltic Finnic words: kirik, kirkko, that is words in 23 languages, hence Uropi kerk. The second one, apart from modern Greek eklisia, gave all Romance words: église, iglesia, chiesa…, Celtic words: iliz, eglwys, eaglais, as well as Albanian kishë, Turkish kilise, Georgian eklesia, Armenian yekeghets'i, Azeri kilsə, that is words in 15 languages.

Apart from this, we have 3 Slavic words stemming from Late Latin castellum (castle): Polish kościół, Czech kostel and Slovak kostol, two Baltic words stemming from old Russian bozhnitsa (house of God): Latvian baznīca and Lithuanian bažnyčia, then Rumanian biserică from Greek basilikê (cf basilica), and Hungarian templom (from Latin templum = temple).

Koklùz - conclusion - Schluss - conclusione - zaključenje - symperasma

Di eke sampe id mape dik no ʒe bun wa sin po lingas Unid in Varid, id kim vidì uscepen Uropi vorde: lu se nerim talvos de maj komùn id de maj intranasioni vorde tramìd tale Europan id Indeuropan lingas. Naturim nun linga se perfeti, id ekvos je s'ne mozli uscepo de maj komùn vord par je ste ne komùn vorde, o par de vord se ʒa esistan in Uropi ki un alten sin (po samp "caj" moz ne sino tej par je ste ʒa de adjetìv caj). Pur je se rarim de kaz, id un ve talvos findo vorde we se maj intranasioni te altene, o bemìn sat intranasioni. Eniwim de Uropi bazi vokabular ven od 500 komùn, Indeuropan rode, wa det ja mol intranasioni.

Ces quelques exemples et cartes nous montrent bien ce que signifie, pour les langues, Unité dans la Diversité, et comment ont été choisis les mots Uropi: ce sont presque toujours les termes les plus communs et les plus internationaux parmi toutes les langues européennes et indo-européennes. Bien sûr, aucune langue n'est parfaite, et il est parfois impossible de choisir le terme le plus commun car il n'y a pas de terme commun, ou bien parce que le mot existe déjà en Uropi avec un autre sens (par exemple "caj" ne peut pas vouloir dire thé parce qu'il y a déjà l'adjectif caj = chaud). C'est pourtant rarement le cas, et on trouvera toujours des termes qui sont plus internationaux que d'autres, ou suffisamment internationaux. Quoi qu'il en soit, le lexique Uropi de base est issu de 500 racines indo-européennes communes, ce qui le rend très international.

These few examples and maps show us very well what Unity in Diversity means for languages, and how Uropi words were chosen: they are nearly always the most common and the most international words among all European and Indo-European languages. Of course no language is perfect, and sometimes it's not possible to choose the most common term because there is no common term, or because the word already exists in Uropi with another meaning (for instance "caj" cannot mean tea because there already is the adjective caj = hot). However this is rarely the case, and we can always find words that are more international than others, or at least sufficiently international. In any case the Uropi basic vocabulary stems from 500 common Indo-Europan roots, which makes it very international.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F2%2F7%2F277026.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F42%2F21%2F321345%2F133835185_o.jpeg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F60%2F50%2F321345%2F131836320_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F73%2F77%2F321345%2F130540623_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F46%2F98%2F321345%2F129165442_o.jpg)