Uropi: U komùn intranasioni linga 1 - Langue commune internationale - A common international language

* Uropi Nove 114 * Uropi Nove 114 * Uropi Nove 114 *

★ ★ ★

★ ★ ★

1) Kim mako un intranasioni eldilinga !

* * * *

Prim, san Franci,

I doʒev deto ap ki u Francicentru vizipunt.

Po samp,

instà uzo de verb avo wim in usprese wim: j’ai faim, j’ai soif, in Franci, uzo: so + adjetìv wim in Engli: I’m hungry, I’m thirsty > Ur. i se fami, i se sisti

o jok slimes, nemo u solen verb wim in Greci: πεινάω, διψάω ‘pináo, dipsáo’ = i fam, i sist

Esperanto det ja os, ba je vid suprù koplizen: mi MALsatas

2) Deto ap ki u purim Romaniki-centru vizipunt.

Po samp Romaniki lingas av u futùr formen ki infinitiv + de fendade de verbi avo: Fr chanter-ai, Esp cantar-é, It canter-ò…

instà, uscepo un analìzi futùr wim in Germàni id Balkàni lingas (ki u partikel o eldiverb for de verb): I will sing, ich werde singen, Gr θα τραγουδήσω ‘tha tragoudisô’, Bul ще пея ‘cte peja’ > Ur. i ve santo

Di struad esìst os in eke Romaniki lingas: Fr je vais chanter, Esp voy a cantar, Rum. voi cânta…

3) Deto ap ki u purim Eurocentru vizipunt.

Un od de karakteristike Indeuropan lingus, se personi verbi fendade: cant-O, cant-AS, cant-A

Po prosàn un moz uzo de anvarizli verbirod ki personi pronome, wim in Cini: SHUŌ = voko:

Ur. i , tu, he, ce, je, nu, vu, lu VOK = Ci. wŏ, nĭ, tā, wŏmen, nĭmen, tāmen SHUŌ

Uvedà, in Hungàri, un moz formo adjetìve ajutan -i a eni nom:

ház > házi, víz > vízi, tenger > tengeri, Eger (Hungàri pol) > Egri

= in Uropi: has > hasi, vod >vodi, mar > mari, pater > patri

Un find os adjetive fenden ki -i in Arabi: ghabi, gharbi, ghāli, ramādi, wardi (stupi, westi, diari, gris, rozi), in Hebraji: ẖalavi, ẖashmali, mizrahi (liki, elektriki, osti), in Hindi: hīndī, rūsī, cīnī, jāpānī (Hindi, Rusi, Cini, Japoni), in Kurdi: kurdî, fransî, îtalî, japonî = Kurdi, Franci, Itali, Japoni…

Di se mol slimi id mol pratiki:

★ ★ ★

★ ★ ★

1) Comment créer une LAI ?

*****

Tout d’abord, en tant que Français,

Il faut se débarrasser d’un point de vue Francocentrique.

Par exemple,

au lieu d’utiliser avoir comme dans j’ai faim, j’ai soif, suivre l’anglais: être + adjectif: I’m hungry, I’m thirsty je suis affamé, assoifé > Uropi: i se fami, i se sisti

ou encore plus simplement, choisir un verbe unique comme en Grec: πεινάω, διψάω ‘pináo, dipsáo’

>En Uropi: i fam, i sist

C’est le cas en Esperanto, mais ça se complique tout de suite: mi MALsatas

2) Se débarrasser d’un point de vue exclusivement Romano-centrique,

Par exemple les langues romanes ont un futur fait de l’infinitif auquel on ajoute les terminaisons du verbe avoir: Fr chanter-ai, esp cantar-é, it canter-ò

choisir plutôt un futur analytique: Ur. i ve santo, comme dans les langues germaniques et balkaniques (avec particule ou auxiliaire + verbe): I will sing, ich werde singen, Gr θα τραγουδήσω ‘tha tragoudisô’, Bul ще пея ‘chté peya’

Cette construction existe aussi dans certaines des L. romanes: fr je vais chanter, esp voy a cantar, roum. voi cânta…

3) Se débarrasser d’un point de vue exclusivement Eurocentrique.

Une des caractéristiques des langues indo-européennes, c’est la flexion personnelle du verbe: cant-O, cant-AS, cant-A

Pour le présent on peut utiliser la racine verbale invariable, accompagnée des pronoms personnels, comme en Chinois: SHUŌ, Uropi VOKO = parler:

Ur. i , tu, he, ce, je, nu, vu, lu VOK = Chi. wŏ, nĭ, tā, wŏmen, nĭmen, tāmen SHUŌ

Par ailleurs en hongrois, on peut former des adjectifs en ajoutant -i à n’importe quel nom:

ház, házi = maison, de maison, víz, vízi = eau, d’eau, tenger, tengeri = mer, de mer, Eger (ville hongroise), Egri = d’Eger.

On trouve aussi des adjectifs en -i en arabe: ghabi, gharbi, ghāli, ramādi, wardi (stupide, de l’ouest, cher, gris, rose), en hébreu: ẖalavi, ẖashmali, mizrahi (de lait, élektrisue, de l’est), en hindi: hīndī, rūsī, cīnī, jāpānī (hindi, russe, chinois, japonais), en kurde: kurdî, fransî, îtalî, japonî = kurde, français, italien, japonais…

en Uropi: has > hasi, vod >vodi, mar > mari, pater > patri (maison/maison, eau/aquatique, mer/marin père, paternel).

C’est très simple et très pratique:

★ ★ ★

1) How to make an IAL !

*****

First, being French,

I would have to get rid of a Francocentric point of view.

For example

the idiomatic use of the verb to have as in j’ai faim, j’ai soif = I’m hungry, I’m thirsty > in Uropi: i se fami, i se sisti

or even more simply, use instead, a single verb as in Greek: πεινάω, διψάω ‘pináo, dipsáo’

> In Uropi: i fam, i sist

Esperanto does it, but makes it complicated at once: mi MALsatas

2) Get rid of an exclusively Latino-centric point of view.

For example Romance languages have a future made of the infinitive + the endings of the verb to have:

Fr chanter-ai, Sp cantar-é, It canter-ò

instead have an analytic future: Ur. i ve santo as in Germanic and Balkan languages (with a particle or auxiliary before the verb): I will sing, ich werde singen, Gr θα τραγουδήσω ‘tha tragoudisô’, Bul ще пея ‘shte peya’

This construction also exists in some Romance L. Fr je vais chanter, Sp voy a cantar, Rum. voi cânta…

3) Get rid of an exclusively Eurocentric point of view.

One of the characteristics of Indo-European languages is a personal inflection of the verb: cant-O, cant-AS, cant-A

For the present we could use an invariable verb root as in Chinese: SHUŌ = speak (Uropi: VOKO)

Ur. i , tu, he, ce, je, nu, vu, lu VOK = Chi. wŏ, nĭ, tā, wŏmen, nĭmen, tāmen SHUŌ

Moreover, in Hungarian, adjectives can be formed by adding -i to any noun:

ház, házi = house(-), víz, vízi = water(-), tenger, tengeri = sea(-), Eger (an Hungarian town), Egri

in Uropi: has > hasi, vod > vodi, mar > mari, pater > patri = (house-, water-, sea-, father’s)

You can also find adjectives ending in -i in Arabic: ghabi, gharbi, ghāli, ramādi, wardi (stupid, western, expensive, grey, pink), in Hebrew: ẖalavi, ẖashmali, mizrahi (milky, elektrical, eastern), in Hindi: hīndī, rūsī, cīnī, jāpānī (Hindi, Russian, Chinese, Japanese), in Kurdish: kurdî, fransî, îtalî, japonî = Kurdish, French, Italian, Japanese…

This is very simple and convenient:

★ ★ ★

★ ★ ★

2) Kim so intranasioni ?

* * * *

Un intranasioni linga doʒev avo de maj intranasioni vorde mozli.

Pardà, i av uscepen bazo de Uropi vokabular su Indeuropan lingas, de grenes lingu famìl in mold.

Indeuropan lingas vid voken pa nerim 3 miliarde liente, su de pin kontinente: in Europa naturim, ba os in Midostia (Persi, Pactu, Kurdi…), in Rusia id Sibiria, in India (Hindi, Bengali, Panʒabi…), in Amerika (Engli, Espàni, Portugi, Franci), in Afrika wo Franci, Engli, Portugi se ofisial lingas, id wo Afrikane doʒ uzo la po komuniko ki alten Afrikane…i.s.p. Pardà de slimi Uropi vorde se bazen su de Indeuropan rode we se komùn a mole I-E lingas, wim, po samp: mata, sol, moro o sedo.

Ba vu ve prago: parkà uskluzo lingas wim Cini we se un od de maj voken lingas in mold ?

De problèm ki Cini vorde se te lu se rarim, po ne dezo nevos intranasioni. Usim de du vorde po ‘tej’: ‘te’ id ‘chai’, obe Cini, un av mojse ‘jin’ id ‘jang’, ‘tai chi’, ‘feng shui’… di se nerim tal. Ruvirtim, Cini av os ne ‘inporten’ uslandi vorde, gonim a Japoni we av intrameten mole vorde ki alten lingas. Di se partim deben a de struktùr Cini vordis we se unisilabi, wa det ja mol anlezi adopto varisilabi vorde; begòn, de Japoni vordistruktùr, we se silabi, det ja maj lezi, oʒe is inporten vorde vid molvos disformen (po samp, Engli ‘straik’ vid ‘sutoraiku’).

Uvedà, Cini se u linga ki tune: u vord moz semo de som in Europan oje, ba wan je av disemi tune, je av os disemi sine. Po samp: mā sin ‘mama’ id mǎ sin ‘kwal’. Indèt lu vid skriven ki disemi ideograme: 妈 id 马. Sim je se mol anlezi uzo la in un IEL.

Televìz, usfinden pa u Skot John Logie Baird av u Greci-Latini nom: tele- = dal + visio = viz, we esìst in maj te 44 lingas, inkluzan Afrikan lingas wim Swahili id Zulu, Azian lingas wim Turki, Indonesi, Filipini, Mongoli, Korean id Japoni: terebijan o terebi, ba ne in Cini wo un dez diàn shì (elektrik + speko). Somim de vord komputèl (od Engli computer, od Latini computare = konto) esìst in 42 lingas tra tal mold, ba ne in Cini wo un dez diàn năo (elektrik + cern).

Nemem po samp de verb volo we se yào in Cini, ba wen un find in nun alten linga: nè in Japoni, nè in Korean, nè in Vietnami, nè in Laosi, nè in Mongoli… Is gonim un nem de rod vol we se Indeuropan (od PIE *wel-), un find ja in 26 lingas (volo, volere, voler, vouloir, wollen, willen, ville, vilja, vēlēt…) = volo id (voluntad, vontade, voință, will, valia, volia, wola, volja, vůle, vôle, voulisi, vullnet…) = volad…, id os in Esperanti (voli) id in Sambahsa (voliem).

Un alten samp se de verbi negad: bu we esìst solem in Cini), id de Indeuropan negad *ne wen un find in 36 veti id moderni lingas, o de personi pronòm (trij persòn singular) tā = he, ce, je solem in Cini , trawàn tu (duj persòn singular) esìst in 50 Indeuropan lingas (od Hindi tū, tum a Rusi ty, od Swedi du a Itali tu, od Persi tu, a Albani ti, od Gaeli tú a Lituvi tu…), ane voko ov Esti, Fini te id Hungari te, ti.

★ ★ ★

★ ★ ★

Pur, Uropi se ne ane vige ki Cini:

Un doʒ rumarko te Uropi bazi vorde se unisilabi wim Cini vorde, po samp bij = C. bái, baj = wān, wan = hé, he = tā, blu = lán, lan = màn, man = nán, rol = lún, lun = yuè, tas = bēi, bej = fēng, kun = gŏu, gov = chún, sia = zì, zi = cĭ, ling = shé, ce = tā, alm = ling, kis = wĕn, wen = shéi, po = wèi, klin = pō, beb = wá, wa = shú, vaj = tú, tu = nĭ, ni = bì, tan = lèi, lej = qīng, sof = tàn, tio = tài, taj = léi, jar = suì, suj = zàng, sun = jiàn, dam = sŭn, su = shàng, siud = sú, men = sī, dor = mén, sand = shā, ca = tā, tri = sān, san = cúnzài, klas = pĭn, pin = wŭ, ba = dàn, oc = bā, pan = miànbāo, plat = pán, pa = yóu, fraj = pà, ne = bu …

U poj wim is un avev displasen tal id de vorde findev nemaj li veri sine.

Ba in u linga, je ste ne solem bazi rodivorde, je ste os ‘struen’ vorde we vid formen in vari mode, po samp koseten vorde. Uropi form ji koseten vorde in de som mod te Cini:

C. bèi = ruk + bāo = sak > bèibāo = rukisak, bīng = jas + xié = cus > bīngxié = slizicùs, cān = jedo + tīng = sal > cāntīng = jedisàl, dàn = ov + bái = bij > dànbái = ovibìj, dàn = ov + huáng = ʒel > dànhuáng = oviʒèl, dēng = lamp + tă = tor > dēngtă = lucitòr, dì = ter + zhèn = skuto > dìzhèn = teriskut, ĕr = or + huán = ring > ĕrhuán = oriring, guŏ = frut + zhī = suc > guŏzhī = frutisuc, jīn = gor + yǘ = pic > jīnyǘ = goripìc, lún = rol + yĭ = sel > lúnyĭ = rolisèl, mì = miel + yüè = lun > mìyüè = mielilun, tiĕ = ern + lù = vaj > tiĕlù = ernivaj, ruò = flabi + diăn = punt > ruòdiăn = flabipunt, shuĭ = vod + mò = mulia > shuĭmò = vodimulia,…

Idmaj, koeglan lingas, je se os insani koeglo gramatik id sintàks, id ne solem vorde. Za un viz te de Uropi konjugad verbis se maj neri a Cini te a Indeuropan lingas. Nu av ʒa vizen de prosàn (vize sube)

Po futùr, Cini uz vari partikle ki de verb: jiāng (skriven linga), huì (voken linga) id oʒe yào (volo), wim in Uropi de partikel ve (we ven od volo): wŏ yào qù fàguó = i ve ito (a) Francia (= i vol…), nĭ huì chī ròu = tu ve jedo mias, tā bù huì hē píjiŭ = he v’ne pivo bir, tā jiāng qù zhōngguó xuéxí = he v’ito a Cinia (po) studo.

De frazi sintàks se maj o min de som in Uropi id Cini: S.V.O: wŏmen yào chī hóng ròu = nu vol jedo roj mias

Sim po un IEL, so intranasioni, sin ʒe ne nemo vorde usfalim od tale lingas moldi, ba priʒe uscepo de vorde we se ʒa de maj intranasioni, id renemo sintakse id gramatiki strukture we se ʒe mol slimi.

* * * *

2) Comment être international ?

* * * *

Une langue internationale se doit de choisir les mots les plus internationaux possibles.

C’est pourquoi, nous avons décidé de baser le vocabulaire Uropi sur les langues indo-européennes, la plus grande famille linguistique au monde.

Lande wo Indeuropan lingas vid voken wim pri o duj ofisial linga

★ ★ ★

Les langues indo-européennes sont parlées par près de 3 milliards de locuteurs, sur les cinq continents: en Europe bien sûr, mais aussi au Moyen Orient (perse, pachto, kurde…), en Russie et en Sibérie, en Inde (hindi, bengali, panjabi…), en Amérique (anglais, espagnol, portugais, français), en Afrique où le français, l’anglais, le portugais sont des langues officielles, et où les Africains les utilisent pour communiquer avec d’autres Africains…etc. C’est pour cela que les mots Uropi courants sont basés sur les racines indo-européennes communes à de nombreuses langues i-e, comme, par exemple: mata, sol, moro, sedo (mère, soleil, mourir, être assis)

Mais, me demanderez-vous, pourquoi exclure des langues comme le chinois qui est une des langues les plus parlées au monde ?

Le problème avec les mots chinois, c’est qu’ils sont rarement, pour ne pas dire jamais internationaux. En dehors des deux termes pour le ‘thé’: ‘te’ et ‘chai’, tous deux chinois, on a peut être ‘yin’ et ‘jang’, ‘tai chi’, ‘feng shui’…, et c’est à peu près tout. Par ailleurs, le chinois n’a pas non plus ‘importé’ de termes étrangers, contrairement au japonais qui a échangé beaucoup de mots avec les autres langues. Ceci est dû en partie à la structure monosyllabique des mots chinois qui rend l’adoption de termes plurisyllabiques plutôt difficile; en revanche, la structure polysyllabique des mots japonais facilite les choses, même si les termes importés sont souvent déformés (par exemple, l'anglais ‘strike’ devient ‘sutoraiku’).

En outre, le chinois est une langue à tons: un mot peut sembler le même aux yeux d’un Européen, mais lorsqu’il a des tons différents, il a aussi des sens différents. Par exemple: mā signifie ‘maman’ et mǎ ‘cheval’. D’ailleurs on les écrit avec deux idéogrammes différents: 妈 et 马, ce qui est difficilement exportable dans une LAI.

La télévision, inventée par un Ecossais John Logie Baird, a un nom gréco-latin: tele- = loin + visio = vue, que l’on retrouve dans plus de 44 langues, y compris dans des langues africaines comme le swahili et le zoulou, des langues asiatiques comme le turc, l’indonésien, le philippin, le mongol, le coréen et le japonais: terebijan ou terebi, mais pas en chinois où l’on dit diàn shì (électrique + regarder). De même le mot anglais computer, (du latin computare = compter) existe dans 42 langues à travers le monde, mais pas en chinois où l’on dit diàn năo (électrique + cerveau).

Prenons par exemple le verbe vouloir qui est yào en mandarin, mais que l’on ne retrouve dans aucune autre langue: ni en japonais, ni en coréen, ni en vietnamien, ni en laotien, ni en mongol… si au contraire on prend la racine vol qui est indo-européenne (du PIE *wel-), on la retrouve dans 26 langues (volo, volere, voler, vouloir, wollen, willen, ville, vilja, vēlēt…) = vouloir et (voluntad, vontade, voin-ță, will, valia, volia, wola, volja, vůle, vôle, voulisi, vullnet…) = volonté…, et également en espéranto (voli) et en Sambahsa (voliem).

Un autre exemple est la négation du verbe: bu qui n’existe qu’en chinois, et la négation indo-européenne *ne que l’on retrouve dans 36 langues anciennes et modernes, ou le pronom personnel (troisième personne du singulier) tā = il ou elle, seulement en chinois, alors que tu (deuxième personne du singulier) existe dans 50 langues indo-européennes (du hindi tū, tum au russe ty, du suédois du à l’italien tu, du perse tu, à l’albanais ti, du gaélique tú au lituanien tu…), sans parler de l’estonien, du finnois te et du hongrois te, ti.

★ ★ ★

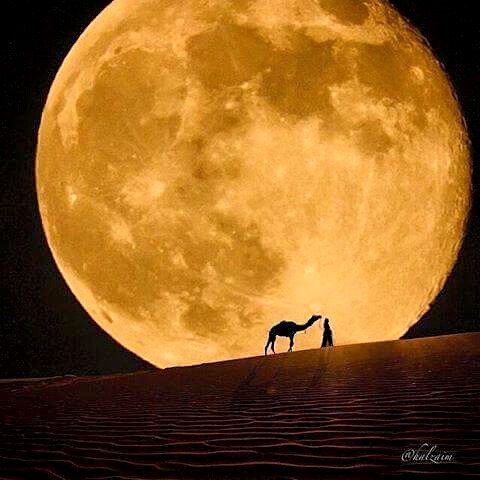

Civa Natarāja, de dansiraj

★ ★ ★

L’ Uropi cependant n’est dépourvu de liens avec le chinois.

Remarquons tout d’abord que les mots Uropi de base sont des monosyllabes tout comme le sont les mots chinois, par exemple Ur. bij = C. bái = blanc, baj = wān = baie, wan = hé = quand, he = tā = il, blu = lán = bleu, lan = màn = lent, man = nán = homme, rol = lún = roue, lun = yuè = lune, tas = bēi = tasse, bej = fēng = abeille, kun = gŏu = chien, gov = chún = boeuf, sia = zì = soi, zi = cĭ = ici, ling = shé = langue, ce = tā = elle, alm = ling = âme, kis = wĕn = baiser, wen = shéi = que, po = wèi = pour, klin = pō = pente, beb = wá = bébé, wa = shú = ce que, vaj = tú = chemin, tu = nĭ = tu, ni = bì, = notre, tan = lèi = fatigué, lej = qīng = léger, sof = tàn = soupir, tio = tài = trop, taj = léi = lien, jar = suì = année, suj = zàng = sale, sun = jiàn = sain, dam = sŭn = dommage, su = shàng = sur, siud = sú = coutume, men = sī = pensée, dor = mén = porte, sand = shā = sable, ca = tā = la, elle, tri = sān = trois, san = cúnzài = être, klas = pĭn = classe, pin = wŭ = cinq, ba = dàn = mais, oc = bā = huit, pan = miànbāo = pain, plat = pán = plat, pa = yóu = par, fraj = pà = peur, ne = bu = ne pas, …

C’est un peu comme si on avait tout déplacé et que les mots ne retrouvaient plus leur véritable sens.

Mais une langue ne se limite pas aux mots-racines de base; elle comporte aussi des mots ‘construits’ qui sont formés de diverses manières, par exemple les mots composés. L’ Uropi forme ses mots composés de la même façon que le chinois:

C. bèi = ruk (dos) + bāo = sak (sac) > bèibāo = rukisak (sac à dos), bīng = jas (glace) + xié = cus (chaussure) > bīngxié = slizicùs (patin à glace), cān = jedo (manger) + tīng = sal (salle) > cāntīng = jedisàl (salle à manger), dàn = ov (oeuf) + bái = bij (blanc) > dànbái = ovibìj (blanc d’oeuf), dàn = ov (oeuf) + huáng = ʒel (jaune) > dànhuáng = oviʒèl (jaune d’oeuf), dēng = lamp (lampe) + tă = tor (tour) > dēngtă = lucitòr (phare), dì = ter (terre) + zhèn = skuto (secouer) > dìzhèn = teriskut (tremblement de terre), ĕr = or (oreille) + huán = ring (anneau) > ĕrhuán = oriring (boucle d’oreille), guŏ = frut (fruit) + zhī = suc (jus) > guŏzhī = frutisuc (jus de fruit), jīn = gor (or) + yǘ = pic (poisson) > jīnyǘ = goripìc (poisson rouge), lún = rol (roue) + yĭ = sel (chaise) > lúnyĭ = rolisèl (fauteuil roulant), mì = miel + yüè = lun (lune) > mìyüè = mielilun (lune de miel), ruò = flabi (faible) + diăn = punt (point) > ruòdiăn = flabipunt (point faible) shuĭ = vod ( eau)+ mò = mulia (moulin) > shuĭmò = vodimulia (moulin à eau)…

En outre, lorsque l’on compare des langues, on ne peut se contenter du vocabulaire, il est essentiel de comparer aussi la grammaire et la syntaxe. Et là, on peut voir que la conjugaison des verbes Uropi est plus proche du chinois que de celle des langues indo-européennes. Nous avons déjà vu le présent (voir ci-dessus).

Pour le futur, le chinois utilise diverses particules devant le verbe: jiāng (langue écrite), huì (langue parlée) et même yào (vouloir), comme en Uropi la particule ve (issue de volo = vouloir) qui précède le verbe: wŏ yào qù fàguó = i ve ito (a) Francia (= j’irai en France (veux aller…), nĭ huì chī ròu = tu ve jedo mias (tu mangeras de la viande), tā bù huì hē píjiŭ = he v’ne pivo bir (il ne boira pas de bière), tā jiāng qù zhōngguó xuéxí = he v’ito a Cinia po studo (il ira étudier en Chine).

La syntaxe de la phrase est plus ou moins la même en Uropi et en chinois: S.V.O: 1 wŏmen 2 yào 3 chī 4 hóng 5 ròu = 1 nu 2 vol 3 jedo 4 roj 5 mias (nous voulons manger de la viande rouge).

On peut donc dire que pour une LAI, être internationale, ne signifie pas emprunter des mots au hasard dans toutes les langues du monde, mais plutôt choisir les termes qui sont déjà les plus internationaux, et reprendre une syntaxe et des structures grammaticales parmi les plus simples et les plus faciles.

★ ★ ★

2) How to be international

*****

An international language should have the most international words possible.

This is why we have chosen to base the Uropi vocabulary on the Indo-European languages, the largest language family in the world.

Indo-European languages are spoken by nearly 3 billion people, on the five continents: in Europe of course, but also in the Middle East (Persian, Pashto, Kurdish…), in Russia and Siberia, in India (Hindi, Bengali, Penjabi…), in America (English, Spanish, Portuguese, French), in Africa where French, English, Portuguese are official languages, and where Africans use them to communicate with other Africans…etc. This is the reason why simple Uropi words are based on the Indo-European roots that are common to numerous I-E languages, like: mata, sol, moro or sedo (mother, sun, to die, to sit), for example.

But you will ask me, why do you exclude languages like Chinese which is one of the most spoken languages in the world ?

Well, the problem with Chinese words is that they are rarely, not to say never, international. Apart from the two terms for ‘tea’: ‘te’ and ‘chai’, both Chinese, we also have perhaps ‘yin’ and ‘yang’, ‘tai chi’, ‘feng shui’… and that is nearly all. On the other hand, Chinese has not ‘imported’ foreign words either, unlike Japanese which has exchanged many words with other languages. This is partly due to the monosyllabic structure of Chinese words which makes it very difficult to adopt polysyllabic terms. The Japanese word structure, on the other hand, which is polysyllabic makes it easier, although imported words are often distorted (for example, ‘strike’ becomes ‘sutoraiku’).

Besides, Chinese is a tonal language: a word may seem the same in the eyes of a European, but with different tones, it has different meanings. For example: mā means ‘mum’ and mǎ ‘horse’. And in fact they are written with two different ideograms: 妈 et 马. All this can hardly be used in an IAL.

Television, invented by a Scot, John Logie Baird, has a Greco-Latin name: tele- = far + visio = sight, view, that can be found in over 44 languages, including African languages like Swahili and Zulu, Asian languages like Turkish, Indonesian, Philippino, Mongolian, Korean and Japanese: terebijon or terebi, but not in Chinese which says diàn shì (electrical + to watch). Similarly the word computer, (from Latin computare = to count) exists in 42 languages all over the world, but not in Chinese which says diàn năo (electric + brain).

Let’s take for example the verb to want: yào in Mandarin, but this word can’t be found in any other language, either in Japanese, or Korean, Vietnamese, Laotian, Mongolian… If on the other hand you take the root ‘vol’ (from PIE *wel-)= to want, you will find it in 26 languages (volo, volere, voler, vouloir, wollen, willen, ville, vilja, vēlēt…) = to want and (voluntad, vontade, voință, will, valia, volia, wola, volja, vůle, vôle, voulisi, vullnet…) = will…, and also in Esperanto (voli) and Sambahsa (voliem).

Another example is the negative particle: bu that exists only in Chinese, and the Indo-European particle *ne which can be found in 36 ancient and modern languages, or the personal pronoun (third person singular) tā = he, she, it, only in Chinese, whereas the second person singular tu (from PIE *tū) exists in 50 Indo-European languages (from Hindi tū, tum to Russian ty, from Swedish du to Italian tu, from Persian tu, to Albanian ti, from Gaelic tú to Lithuanian tu…, etc.), not to mention Estonian, and Finnish te and Hungarian te, ti.

★ ★ ★

★ ★ ★

However Uropi is not completely unrelated to Chinese.

We may notice that Uropi basic words are monosyllabic like Chinese words,

for example bij = C. bái = white, baj = wān = bay, wan = hé = when, he = tā = he, blu = lán = blue, lan = màn = slow, man = nán = man, male, rol = lún = wheel, lun = yuè = moon, tas = bēi = cup, bej = fēng = bee, kun = gŏu = dog, gov = chún = ox, sia = zì = oneself, zi = cĭ = here, ling = shé = tongue, ce = tā = she, alm = ling = soul, kis = wĕn = kiss, wen = shéi = whom, po = wèi = for, klin = pō = slope, beb = wá = baby, wa = shú = what, vaj = tú = way, tu = nĭ = you, ni = bì = our, tan = lèi = tired, lej = qīng = light, sof = tàn = sigh, tio = tài = too, taj = léi = tie, bond, jar = suì = year, suj = zàng = dirty, sun = jiàn = healthy, dam = sŭn = damage, su = shàng = on, siud = sú = custom, men = sī = thought, dor = mén = door, sand = shā = sand, ca = tā = her, tri = sān = three, san = cúnzài = being, klas = pĭn = class, pin = wŭ = five, ba = dàn = but, oc = bā = eight, pan = miànbāo = bread, plat = pán = dish, pa = yóu = by, fraj = pà = fear, ne = bu = not, …

It is as if everything had been moved about and words could no longer find their original meaning.

But a language is not only made up of basic words; there are also ‘constructed’ words formed in different ways, for example compounds. Uropi compounds are formed exactly in the same way as in Chinese:

C. bèi = ruk (back) + bāo = sak (sack) > bèibāo = rukisak (rucksack), bīng = jas (ice) + xié = cus (shoe) > bīngxié = slizicùs (ice skate), cān = jedo (eat) + tīng = sal (room) > cāntīng = jedisàl (dining room), dàn = ov (egg) + bái = bij (white) > dànbái = ovibìj (egg white), dàn = ov (egg) + huáng = ʒel (yellow) > dànhuáng = oviʒèl (yolk), dēng = lamp (lamp) + tă = tor (tower)> dēngtă = lucitòr (lighthouse), dì = ter (earth) + zhèn = skuto (shake) > dìzhèn = teriskut (earthquake), ĕr = or (ear) + huán = ring (ring) > ĕrhuán = oriring (earring), guŏ = frut (fruit) + zhī = suc (juice) > guŏzhī = frutisuc (fruit juice), jīn = gor (gold) + yǘ = pic (fish) > jīnyǘ = goripìc (goldfish), lún = rol (wheel) + yĭ = sel (chair) > lúnyĭ = rolisèl (wheelchair), mì = miel (honey) + yüè = lun (moon) > mìyüè = mielilun (honeymoon), lù = vaj (way) + tiĕ = ern (iron) > tiĕlù = ernivaj (railway), ruò = flabi (weak) + diăn = punt (point) > ruòdiăn = flabipunt (weak point), shuĭ = vod (water)+ mò = mulia (mill) > shuĭmò = vodimulia (water mill)…

Besides, when youn compare languages, it is also essential to compare the grammar and syntax, not only the vocabulary. There, you can see that the conjugation of Uropi verbs is closer to Chinese than to Indo-European languages. We have already seen the present (see above).

In the future tense, Chinese uses various particles before the verb: jiāng (written language), huì (spoken language) and even yào (to want), as in Uropi the particle ve (stemming from volo = want) before the verb: C. wŏ yào qù fàguó = Ur. i ve ito (a) Francia (= I’ll go to France (want to go…), nĭ huì chī ròu = tu ve jedo mias (you will eat meat), tā bù huì hē píjiŭ = he v’ne pivo bir (he won’t drink beer), tā jiāng qù zhōngguó xuéxí = he v’ito a Cinia po studo (He’ll go to China to study).

The syntax of the sentence is more or less the same in Uropi and in Chinese: SVO: 1 wŏmen 2 yào 3 chī 4 hóng 5 ròu = 1 nu 2 vol 3 jedo 4 roj 5 mias (we want to eat red meat).

Thus we can say that for an IAL, being international doesn’t mean borrowing words at random from all the languages in the world, but rather choosing the terms that are already the most international, and adopting a syntax and grammatical structures among the simplest and easiest.

★ ★ ★

★ ★ ★

3) Kim stajo slimi ?

* * * *

Un IEL (intranasioni eldilinga) doʒev so slimi, os slimi te mozli. Slimid se mol vezi par de majsan liente vol ne deto de sfor lero anlezi lingas (po samp ki koplizen disklinade id konjugade).

Wim de gren linguìst Otto Jespersen dezì:

« De bunes eldilinga se daz we provìt de grenes lezid a de grenes numar lientis. »

Un ve ne obvigo Cine uzo de ustrim koplizen sistèm de Indeuropan disklinadis id konjugadis.

Ruvirtim, un moz ne obvigo « Westiane » o altene uzo de sistèm tunis o ideogramis Mandorini.

Sim nu doʒ talvos uscepo u "midan vaj" we se de maj slimi mozli, id we moz vido acepen pa tale.

Prim, bazi vorde doʒev so slimi, unisilabi wim mole Cini vorde (Vize sube), po samp: sol, vod, men, gor, fal, luc, dav, moz, keb, nas… te, la, hi, de, op, ne, od, ki…

De usvòk os doʒev so slimi: po samp nu nud ne maj te 5 vokàle : a, e, i, o, u, id eke diftonge (po s. ai, ei, oi, ui, au…), wim in Itali. Idmàj, u slimi usvòk se de klij a eufonij, harmonij id belad, wim in Japoni haikùs, Azian pictene o poème pa François Cheng.

De regiskrìv doʒev os so slimi, wim in Espàni, po samp: un litèr = un zon; un zon = un litèr. Ne wim in moderni Greci wo / i / moz vido skriven. ι, η, υ, ει, οι… id / b / vid skriven μπ (mp), id / d / ντ (nt)…, o Engli, wo ‘a’ vid usvoken /ə, ei, æ, ɑ:, ɔ:, i…/

De gramatik doʒev os so slimi. Po samp, in Uropi, de verb in prosàn vid konjugen ki de anvarizli verbirod be tale persone, id personi pronome, (wim in Cini, vize sube): i, tu, he, nu, vu, lu vok, disemim od Itali, po samp: parlo, parli, parla, parliamo, parlate, parlano.

De sintàks, id maj generalim de mod uspreso zoce doʒev so os slimi te mozli :

Po samp, Uropi: famo > i fam. instà Fr. j’ai faim o Eng. I am hungry (Vize sube)

Eki vigivorde se annudi id det ja maj anlezi lero de linga (un uslandor zav nevos kel prepozisiòn uzo). Po samp: i doʒ ito kopo (4 vorde), in Franci se il faut que j’aille faire les courses (8V), in Itali devo andare a fare la spesa (6V), in Engli I have to go shopping (5V), in Mandorini: wǒ dé qù gòuwù (4V), in Hindi: mujhe kharīdārī karne jāna hai (5V)… Ce dezì mo ito sopo (5V), in Fr elle m’a dit d’aller me coucher (8V), in It (lei) mi ha detto di andare a letto (7V), in Eng she told me to go to bed (7V), in Greci: μου είπε να πάω για ύπνο (6V), in Mand. tā gàosù wǒ qù shuìjiào (5V)…

Da dezen, pocere! Un doʒ ne komico slimid id uveslimid, un doʒ ne sungo in u stritizan skematisma: un intranasioni eldilinga doʒ mozo uspreso tale de nuanse human meni.

★ ★ ★

★ ★ ★

3) Comment rester simple ?

* * * *

Une langue auxiliaire internationale (LAI) se doit d’être aussi simple que possible. La simplicité est essentielle car la plupart des gens n’ont pas envie de faire l’effort d’apprendre des langues difficiles (par exemple truffées de déclinaisons ou de conjugaisons complexes).

Comme l’a dit le grand linguiste Otto Jespersen:

« La meilleure langue internationale est celle qui offre la plus grande facilité au plus grand nombre. »

On ne va pas imposer aux Chinois le système extrêmement compliqué des déclinaisons et conjugaisons indo-européennes. Inversement, on ne peut pas imposer aux "Occidentaux" ou autres, le système tonal ou idéographique du mandarin. D'où la nécessité de toujours opter pour un "moyen terme" le plus simple possible, qui puisse être accepté de tous.

Tout d’abord, les mots de base peuvent être de simples monosyllabes, par exemple, en Uropi: sol, vod, men, gor, fal, luc, dav, moz, keb, nas… te, la, hi, de, op, ne, od, ki… (comme en mandarin: voir ci-dessus).

La prononciation doit également être la plus simple possible: nous n’avons pas besoin de plus de 5 voyelles : a, e, i, o, u, et de quelques diphtongues (par ex. ai, ei, oi, ui, au…), comme en italien. En outre, une prononciation simple est la clé de l’euphonie, de l’harmonie et de la beauté, comme dans les haikus japonais, les peintures asiatiques ou les poèmes de François Cheng.

L’orthographe doit être simple, elle aussi, comme en espagnol par exemple: une lettre = un son; un son = une lettre, à la différence du grec moderne où le son /i/ peut s’écrire: ι, η, υ, ει, οι… et où /b/ s’écrit μπ (mp), et /d/ ντ (nt)… ou de l’anglais où ‘a’ peut se prononcer: /ə, ei, æ, ɑ:, ɔ:, i…/.

La grammaire doit aussi se caractériser par sa simplicité. Par exemple, en Uropi, le verbe au présent se conjugue avec la base verbale invariable à toutes les personnes, et les pronoms personnels (comme en chinois, voir ci-dessus): i, tu, he, nu, vu, lu vok (je parle, tu parles, il…, nous…, vous…, ils…), à la différence de l’italien, par exemple: parlo, parli, parla, parliamo, parlate, parlano.

La syntaxe, et plus généralement la façon d’exprimer les choses doit être d’une grande simplicité:

Par exemple, l’Uropi: famo > i fam = j’ai faim, comme en grec où l’on utilise un verbe unique pour ‘avoir faim’: πεινάω ‘peinaô’, au lieu de l’ang.: I am hungry, le français: J’ai faim, l’allemand: Ich habe Hunger, le polonais: jestem głodny…

Certains ‘mots de liaison’ sont parfaitement superflus, et rendent l’apprentissage de la langue plus difficile (un étranger ne sait jamais quelle préposition employer). En Uropi, par exemple: i doʒ ito kopo (4 mots) = fr. il faut que j’aille faire les courses (8 M), en italien: devo andare a fare la spesa (6 M), en anglais I have to go shopping (5 M), en mandarin: wǒ dé qù gòuwù (4M), en hindi: mujhe kharīdārī karne jāna hai (5M)…Ur. Ce dezì mo ito sopo (5 M) = elle m’a dit d’aller me coucher (8 M), en it (lei) mi ha detto di andare a letto (7 M), en ang she told me to go to bed (7 M), en grec: μου είπε να πάω για ύπνο (6 M), en mand. tā gàosù wǒ qù shuìjiào (5M)…

Cela dit, attention! Il ne faut pas confondre simplicité et simplisme, ne pas sombrer dans un schématisme réducteur: une langue auxiliaire internationale doit pouvoir exprimer toutes les nuances de la pensée humaine.

★ ★ ★

★ ★ ★

3) How can we remain simple ?

******

An international auxiliary language (IAL) should be as simple as possible. Simplicity is all important because most people don’t want to make the effort of learning difficult languages (for instance full of complex declensions or conjugations).

As the great linguist Otto Jespersen said:

« That international language is best which in every point offers the greatest facility to the greatest number.»

You cannot oblige the Chinese, for example, to use the extremely complicated system of Indo-European declensions and conjugations. On the other hand, ‘Westerners’ or others cannot be obliged to use the tonal or ideographic system of Mandarin. Hence the necessity of always choosing a ‘middle course’ which will be as simple as possible, and acceptable for all.

First of all, basic words could be simple monosyllables, as in Uropi: sol, vod, men, gor, fal, luc, dav, moz, keb, nas… te, la, hi, de, op, ne, od, ki… (or Mandarin: see above).

The pronunciation should also be very simple: we don’t need more than 5 vowels : a, e, i, o, u, and a few diphthongs (for ex. ai, ei, oi, ui, au…), as in Italian. Besides a simple pronunciation is a key to euphony, harmony and beauty, as in Japanese haikus, Asian paintings or the poems of François Cheng.

Spelling should also be as simple as possible, as in Spanish for example: one letter = one sound; one sound = one letter, unlike modern Greek where /i/ can be written: ι, η, υ, ει, οι… and /b/ μπ (mp), and /d/ ντ (nt)

… or English where ‘a’ can be pronounced: /ə, ei, æ, ɑ:, ɔ:, i…/.

We also need a simple grammar. For example, in Uropi, the verb is conjugated as in Chinese (see above), using the invariable verb stem for all persons together with personal pronouns: i, tu, he, nu, vu, lu vok (I speak, you speak he speaks…, we…, you…, they…), unlike Italian, for instance: parlo, parli, parla, parliamo, parlate, parlano.

Syntax, and more generally the way we phrase things should be as simple as possible:

For example Uropi: famo > i fam, instead of Eng. I’m hungry, Fr.: J’ai faim, G. Ich habe Hunger, (See above)

Certain ‘link words’ are unnecessary, and make it more difficult to learn the language (a foreigner, for instance, never knows which preposition to use).

In Uropi: i doʒ ito kopo (4 words) is in French: il faut que j’aille faire les courses (8W), in Italian: devo andare a fare la spesa (6W), and in English: I have to go shopping (5W), in Mandarin: wǒ dé qù gòuwù (4W), in Hindi: mujhe kharīdārī karne jāna hai (5W)…Ur. Ce dezì mo ito sopo (5W) = Fr. elle m’a dit d’aller me coucher (8W), It. (lei) mi ha detto di andare a letto (7W), in Eng: she told me to go to bed (7W), in Greek: μου είπε να πάω για ύπνο (6W), in Mand. tā gàosù wǒ qù shuìjiào (5W)……

But let us be careful! Simplicity does not mean oversimplicity, and we should not sink into a restrictive schematism: an IAL should be able to express all the nuances of human thought.

Partager cet article

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F2%2F7%2F277026.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F42%2F21%2F321345%2F133835185_o.jpeg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F99%2F93%2F321345%2F124897632_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F87%2F24%2F321345%2F120422766_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F54%2F26%2F321345%2F114263105_o.jpg)